…Anyone who has glanced even cursorily at the map of Ireland, will have noticed how the south-west corner of it has suffered from being the furthest outpost of European resistance to the Atlantic. Winter after winter the fight between sea and rock has raged on, and now, after all these centuries of warfare, the ragged fringe of points and headlands, with long, winding inlets between them, look as though some hungry monster’s sharp teeth had torn the soft, green land away, gnawing it out from between the uncompromising lines of rock that stand firm, indigestible and undefeated…

Naboth’s Vineyard, Somerville and Ross, Spencer Blackett, 1891

So constantly entranced am I by the character of this remote corner in which we have chosen to settle (in my own experience – admittedly somewhat geographically limited – it is the most beautiful landscape in the world) that I am always excited when I discover that others have shared the same feelings. Consequently I am forever looking out for references to the coastline and country around Roaringwater Bay – particularly descriptive writing – in the wealth of books on West Cork that are harboured by local bookshops, libraries, and our own shelves here at Nead an Iolair: we are most fortunate that some of these books, especially the now out-of-print ones, came with the house! I have sifted through a few of the words: essays, extracts from novels, historical treatise and guidebooks that support my own feelings about the place. All are taken from writers I admire and thoroughly recommend. I present them here for you to take in, together with some hopefully seductive illustrations from the locality, in support of my thesis that there is no better place to be alive.

…I believe that in West Cork water runs uphill. There is a small lake on the very summit of Mount Gabriel, nearly fourteen hundred steep feet above the Atlantic level. Small it is, but so deep that when, once upon a time, a heifer was lost in it, she came out in Schull harbour, on her way to America! (Or that is what the people tell you.)…

‘Happy Days!’ – Essays of Sorts, Somerville and Ross, Longmans, green and Co, 1946

…There was a line of tables up the middle of the pier, each with its paraffin lamp smoking and flaring in the partial shelter of a fish-box, and each with its wild, Rembrandtish group of women splitting the innumerable mackerel, and rubbing lavish fistfuls of coarse gray salt into each, before it was flung to the men to be packed into barrels. The lamps shone fantastically on the double row of intent faces, on the quickly moving arms of the women, crimsoned to the elbows, on the tables, varnished with the same colour, and on the cold silvery heaps of fish…

Naboth’s Vineyard, Somerville and Ross, Spencer Blackett, 1891

…Think of a wandering road in – let me say West Cork… The way is rough and stony, and (most probably) muddy, but it can claim compensating charms, even though it can hardly fulfil any of the functions proper to respectable roads. And in its favour I would claim the broken varying lines of the hills against the sky. The untidy fences, with their flaming furze bushes, or crimson fuchsia hedges; their throngs of vagabond wild flowers, that can challenge the smug respectability of a well-kept garden. And the inevitable creatures, the donkeys, the pigs, the coupled goats, the geese, that regard the highroad as their lounge and playground. No doubt they exasperate the motorist in a hurry (as are all motorists) but for more tranquil wayfarers they can offer entertainment, almost charm…

‘Happy Days!’ – Essays of Sorts, Somerville and Ross, Longmans, green and Co, 1946

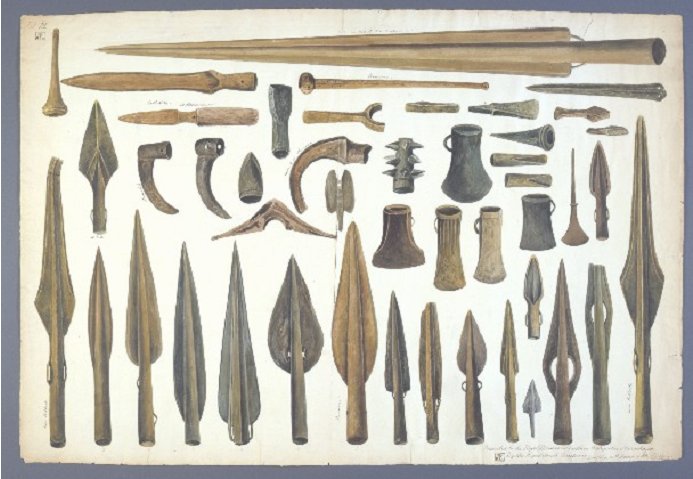

(Ireland) …is a land of surprises. She has the gift of unexpectedness, of uncertainty: her people, like her looks, and her weather, can be sometimes charming, often exasperating, but seldom commonplace. Is there another country, reasonably civilised, in which, in the course of a casual idle stroll, records of pre-history can be met with in any field, unconsidered, or found (as I have known) an immense cup-marked stone, built into the wall of a cow-house, ignored by the descendants of those who were once its worshippers? And yet, in characteristic contrariety – as is our way in Eire – in the field next to that cow-house, you can see that the plough has turned aside from its rightful course in respect for a little old deformity of a thorn-tree, which has asserted, for possibly a thousand years, its right to be reverenced and feared…

(Ireland) …is a land of surprises. She has the gift of unexpectedness, of uncertainty: her people, like her looks, and her weather, can be sometimes charming, often exasperating, but seldom commonplace. Is there another country, reasonably civilised, in which, in the course of a casual idle stroll, records of pre-history can be met with in any field, unconsidered, or found (as I have known) an immense cup-marked stone, built into the wall of a cow-house, ignored by the descendants of those who were once its worshippers? And yet, in characteristic contrariety – as is our way in Eire – in the field next to that cow-house, you can see that the plough has turned aside from its rightful course in respect for a little old deformity of a thorn-tree, which has asserted, for possibly a thousand years, its right to be reverenced and feared…

‘Happy Days!’ – Essays of Sorts, Somerville and Ross, Longmans, green and Co, 1946

…In the mirror that memory will sometimes hold for us, I can see Rahyne Glen at four o’clock on a silver autumn morning before the sun has reached it. Opposite, just below the rim of the steep western side of the glen, there is one of the memorials of an older race and its religion. This is a broad slab of pale stone, leaning sideways against the hill, having, somehow slipped off the stones on which it had been supported. The sunlight falls full on it; it catches the eye and holds it. It is a dolmen, and the pale slab was its cap-stone. It marks the grave of a chief. He might have been content with his resting-place, had beauty of scene appealed to him (which seems improbable). Whether contented or no, he has lain there (if the archaeologists may be believed) undisturbed, through all the long centuries. If he were to look out now on those familiar hills he would see no change. His hills have defied civilization. All would look as it might have looked on any fair September morning during past thousands of years. And, I suppose, the pink ling, and the purple heather and the gold of the low-growing autumn furze, would then have spread the same carpet of colour over the hills… The wild stream comes storming through the thorn-bushes of the glen as fiercely as ever it did when the Chieftain and his warriors washed their spears in it… Beyond the glen the country rises, in long swathes of dim green, and purple, and misty blue, to a curving line of hills, and farther and higher still – for the viewpoint is a high one – a narrow flashing line tells of the silver plain below, which is the Western Ocean…

‘Happy Days!’ – Essays of Sorts, Somerville and Ross, Longmans, green and Co, 1946

…The indented contours of Raring Water Bay enclose a maze of minute inlets and islands. The name derives from a stream which flows down the side of Mount Kidd amidst a landscape of bracken and boulders. The torrent roars in the narrow gaps and gullies as it rushes towards the sea. The little inlets penetrate the land like miniature fjords and create a sense of safe haven from dangerous seas. Their piers, long abandoned except for the occasional fisherman’s or tourist’s boat, are overgrown and tumbled-down romantic ruins, quiet spots for sighting a lone heron at low tide, grey against grey water. In the narrow defile where the roaring water debouches into the bay nature has done much to reclaim the territory usurped by human purpose. Perhaps, like the closing of a wound, this former embarcation point, which saw many thousands flee a country unable to support them, is being bound in ivy and decorated with wild fuchsia to heal the scar…

West of West – An Artist’s Encounter with West Cork – Brian Lalor, Brandon Book Publishers, 1990

…The islands of the West Cork coast are rather grandly referred to as Carbery’s Hundred Islands, but only Clear Island and Sherkin now sustain a viable population – though, like the other islands off the west coast, there is a steady draining of young people to the cities on the mainland for education and employment. Horse Island off Schull is evocative of the vanished communities of these islands. Silhouetted against the skyline, this piece of low-lying land appears like an old-fashioned, gap-toothed saw; a dark bulk of rock with triangular projections – the gable ends of a row of roofless cottages – biting into the clouds…

West of West – An Artist’s Encounter with West Cork – Brian Lalor, Brandon Book Publishers, 1990

…Three or more centuries ago, before the landscape of West Cork became bound by a web of roads and fences, its contours would have been best understood when seen from above, from the heights of Mount Kidd or Mount Gabriel. Parallel ribs of rocks and hills, dividing up the pasture land, extended from the base of the mountains to the coast, where long fingers of rocky promontories projected out into the sea. There was a natural order to everything…

West of West – An Artist’s Encounter with West Cork – Brian Lalor, Brandon Book Publishers, 1990

… Beyond Whitehall I rode out to the point at Cunamore where the road ended at a small pier which was the nearest point to Hare Island, also known as Inishdricoll. There was no regular ferry across, but the post boat went over several days a week, and the schoolmistress crossed daily to teach the dozen remaining children. It is a much less dramatic island than Cape or Sherkin, a low-lying slab of land with golden beaches. One road leads to a little village nicknamed Paris – probably a derivation of ‘pallace’ – once the centre of a fleet of lobster boats. Now I listened to an old man lamenting the terrible decline.

“John has gone and Dennis has died, and we’ll die too, and then the foreigners can have it all.” Already half a dozen of the houses had been bought up by strangers.

One by one the smaller islands became deserted. It is a long time since they were densely populated, but until quite recently they supported a certain number of families. Only a few years ago I visited Horse Island, just opposite Ballydehob. The last people there, an elderly couple, were living all alone. It was summer, and the old man was sitting in a chair outside his house, his feet in a basin of water. His wife, behind him, fed hens. Next year they were gone. The house, still intact and comfortable, stood empty, the linoleum in place, last year’s calendar on the wall. Down by the pier a plough had been thrown into the water where it looked like a gesture of despair…

The Coast of West Cork – Peter Somerville-Large, Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1974

…West of Ballydehob the laneways ran into each other like the veins of a leaf. Many of them were untapped; they seemed empty, with little life except for cattle or a white horse browsing in watery fields beside them. Most seemed to end up at the sea, and each little turn had its own alignment to the bay. One looked across the islands with Kilcoe standing squat and menacing on its headland; the next inlet had a view across to Horse Island; another lane climbed to a hill to where one could see the sweep from Baltimore Beacon and the Gascanane to the shattered tower of Rosbrin castle…

The Coast of West Cork – Peter Somerville-Large, Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1974

…May Day in Schull was the day for ‘bringing in the green’. But the ancient custom is dying out. Only a few branches of green leaves were tied on doors, and a twig of fuchsia dangled from the handle of a bike. “Old pishoges,” an old man muttered as he carefully arranged sycamore round a drainpipe…

The Coast of West Cork – Peter Somerville-Large, Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1974

…Colla harbour and pier is the nearest point to embark for Long Island. Horse Island, Castle Island and Long Island lie in a line just outside Schull harbour. A tradition, quoted by Smith, claims that they were once all one island. “In the latter end of March, AD 830, Hugh Domdighe being monarch of Ireland, there happened . . . terrible shocks of thunder and lightning . . . at the same time the sea broke through the banks in a most violent manner. The island, then called Innisfadda, on the west coast of this country was forced asunder and divided into three parts”…

The Coast of West Cork – Peter Somerville-Large, Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1974

…From the vicinity off Dunanore, we obtain a view of the coast and the surrounding open, which is one of surpassing beauty, when the summer sun is setting in the far west. Towards the south, as far as the eye can reach, the broad expanse of the Atlantic is stretched before our gaze, the distant horizon dotted here and there by some white sail, or the dark hull of one of those leviathan steamers which ply their busy trades between the Old World and the New. Cape Clear is the first land which greets the American tourist or the returning emigrant on his approach to the old country, and the last cherished spot of his ‘own dear isle’ which bids adieu to the Irish peasant, when he parts, perhaps for ever, from his native country…

Sketches in Carbery, County Cork: its antiquities, history, legends, and topography – Daniel Donovan, McGlashan & Gill, 1876