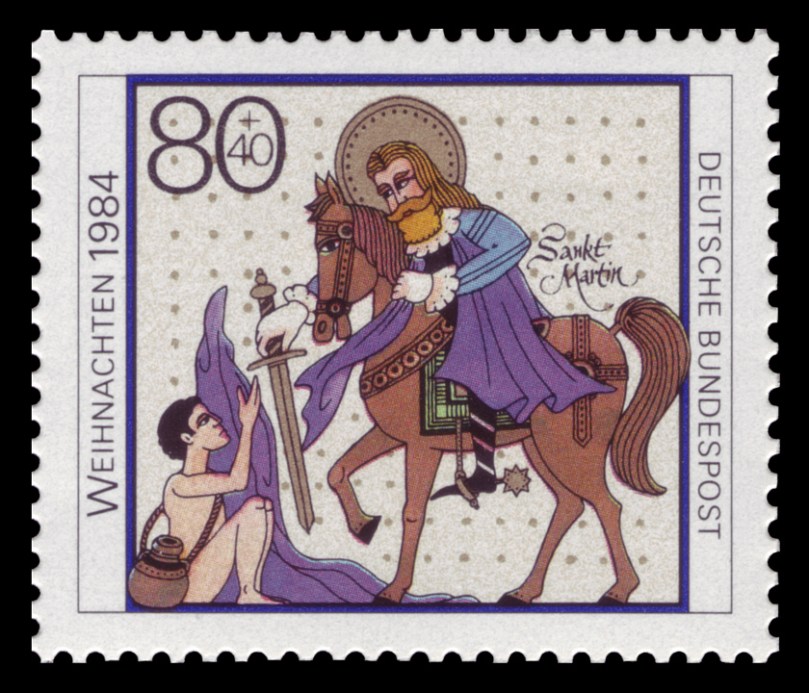

I’m used to pursuing the lives of the Irish Saints – often obscure, always fascinating – their legends tied up with folk tales and seasonal customs. But here we are, in Ireland, with a strong tradition of celebrating a continental Saint – St Martin of Tours.

St Martin doesn’t appear to have any connection with Ireland at all – yet everyone here seems to know the one element of his story that is always told: in the winter storms he met a naked beggar and cut his own cloak in two, giving half to the beggar. There is a twist to the story – that same night Martin had a dream: he saw Jesus wrapped in the piece of cloak he had given away and Jesus said to him, “Martin has covered me with this garment.” Even though Martin was at that time a soldier in the Roman Army he sought to be baptised and then refused to fight as this was against Christian principles. In fact, he was the first recorded ‘Conscientious Objector’.

St Martin’s Day is on 11 November and the season is known in Ireland as Martinmas. There are customs surrounding this time – still remembered in some rural districts. There is a whole chapter devoted to Martinmas in Kevin Danagher’s book The Year in Ireland (Mercier Press 1972). From this we learn that every family is to kill an animal of some kind “…and sprinkle the threshold with the blood, and do the same in the four corners of the house to exclude every kind of evil spirit from the dwelling where this sacrifice is made…”

In 1828 Amhlaoibh Ó Súilleabháin of Kilkenny recorded in his diary: “…The eleventh day, Tuesday. St Martin’s Day. No miller sets a wheel in motion today; no more than a spinning woman would set a spinning wheel going; nor does the farmer put his plough-team to plough. No work is done in which turning is necessary…” This might be because of a story that Martin was martyred when thrown into a mill stream and killed by the mill wheel. In fact the hagiography states that he died of old age.

Another Irish legend (from Wexford) relates that the fishing fleet was out one St Martin’s Day, when the Saint himself was observed walking on the waves towards the boats. He proceeded to tell them to put into harbour as fast as possible, despite the good weather and fishing conditions. All the fishermen who ignored the Saint’s warning drowned during a freak afternoon storm. Traditionally, Wexford fishermen will not go out to sea on Saint Martin’s Day.

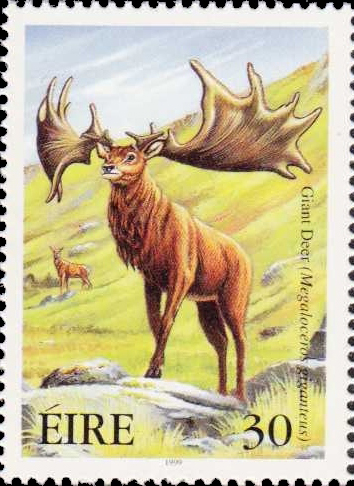

St Martin is the patron saint of Geese. In England there are two ‘Goose Fairs’ held in the autumn, one at Tavistock near my old home on Dartmoor. I have been to that fair: geese and poultry are still in evidence, but I don’t know whether there is any direct link to our Saint. In the not-too-far-away Exeter Cathedral Close there is a Holy Well dedicated to St Martin.

In England and Ireland they call any spell of good weather which occurs after 11th November ‘St Martin’s Summer’. We are having one of those at the moment.

We are also now at the ‘November Dark’ – the days just before a new moon when there is no moon at all visible in the night sky. Traditionally, this was the time to cut willow rods to store for basket making in the spring, as then “…they would have the most bend in them…” (according to Northside of the Mizen).

St Martin’s Goose was traditional fare on Martinmas in some cultures, so I’m feeling a little worried about this gaggle…