…In ancient Ireland the festival of the beginning of the harvest was the first day of Autumn, that is to say, it coincided with 1 August in the Julian calendar. This has continued in recent tradition, insofar as Lúnasa or Lammas-Day was still taken to be the first day of Autumn; the gatherings and celebrations connected with it were, however, transferred to a nearby Sunday, in most parts of Ireland to the last Sunday in July, in some places to the first Sunday in August… The old Lúnasa was, in the main, forgotten as applying to the popular festival and a variety of names substituted in various localities, such as Domhnach Chrom Dubh, Domhnach Deireannach (Last Sunday), Garland Sunday, Hill Sunday and others…

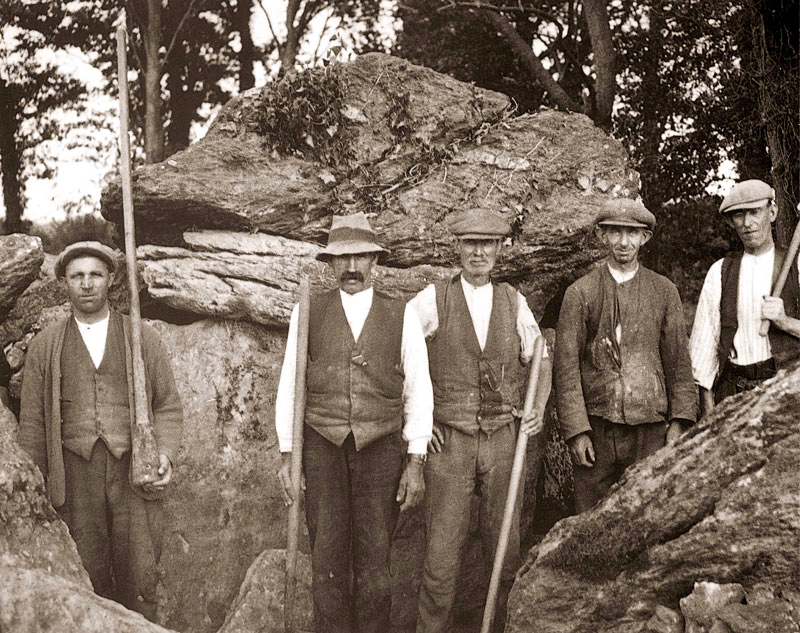

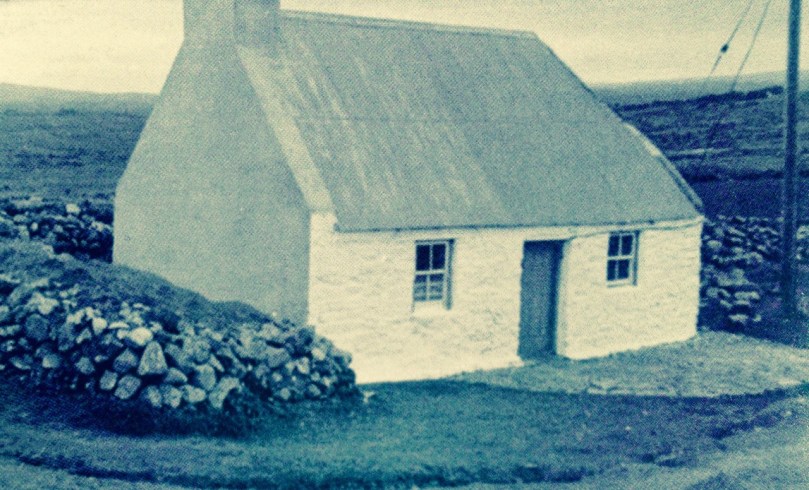

All the photographs in this post are from the collection of Tomás Ó Muircheartaigh who travelled and photographed the west of Ireland during the 1930s, 40s and 50s and is an invaluable documentary of the times in which he lived. Generally, the locations of the photographs are not noted, and very few are likely to be specific to the Mizen: they do however record life as it would have been lived at that time in all the rural areas

Today we celebrate Lúnasa – the festival of the bringing-in of the harvest. Kevin Danaher (The Year in Ireland, Mercier Press 1972) wrote (above) about what he observed in the middle of the last century, when things were already changing and many of the old customs were, as he notes, ‘in the main forgotten’, although still talked about. What changes do we see in Ireland, a few generations on?

Northside of the Mizen by Patrick McCarthy and Richard Hawkes was written in 1999 (Mizen Productions) and is a collection of memories and stories still being told then about traditional life in this westerly part of of the country:

…The heat of the summer was eased by the cooling breezes from the Atlantic. It was busy on land and sea, with seine fishing by night and fish curing and farming by day, but there was always time for scoriachting, games and dance, sometimes on Carbery Island or across Dunmanus Bay…

…Once in the year Carbery Island was the location for a dance and in settled weather the Northsiders could shout across and give the signal to the people of Muintir Bháire to meet at Carbery Island. As many as forty-five people in three boats would cross Dunmanus Bay to the White House, and a good crowd of men and women from Bear Island would also come to the dances. They were great hearty people. Ann Daly from Kilcrohane and Agnes O’Donovan of Dunkelly played the melodeon…

I like the idea of the Northsiders shouting across the water to the residents of the Sheep’s Head, two miles away! I wonder if they would be heard nowadays?

…There were competitions at Dunmanus for swimming, running, jumping and weight lifting, and you could be sure that the Northsiders were well represented in each of the events. ‘Will the Hare’ (William McCarthy of Dunkelly Middle), was good at the long jump and the running races and would often win and bring great honour to the Northside. It was said that ‘Will the Hare’ got his name by catching a hare on the run! It was also said that when you blew the whistle to gather the men for seining, by the time you had finished, ‘Will the Hare’ would be at Canty’s Cove waiting!

…Wild John Murphy would take the lads to the Crookhaven Regatta which was held on The Assumption (15th August). It was a long pull around the Mizen but a good time was had by all. The Northsiders were great with the oars, but it was hard to beat the Long Island crews in the boat races…

(Danaher): …In very many localities the chief event of the festival was not so much the festive meal as the festive gathering out of doors. This took the form of an excursion to some traditional site, usually on a hill or mountain top, or beside a lake or river, where large numbers of people from the surrounding area congregated, travelling thither on foot, on horseback or in carts and other equipages… Many of the participants came prepared to ‘make a day of it’ bringing food and drink and musical instruments, and spending the afternoon and evening in eating, drinking and dancing…

…Another welcome feature of the festive meal was fresh fruit. Those who had currants or gooseberries in their gardens, and this was usual even among small-holders in Munster and South Leinster, made sure that some dish of these appeared on the table. Those who lived near heather hills or woods gathered fraucháin (‘fraughans’, whortleberries, blueberries) which they ate for an ‘aftercourse’ mashed with fresh cream and sugar. Similar treatment was given to wild strawberries and wild raspberries by those lucky ones who lived near the woods where these grow… A number of fairs still held or until recently held at this season bear names like ‘Lammas Fair’, ‘Gooseberry Fair’, ‘Bilberry Fair’…

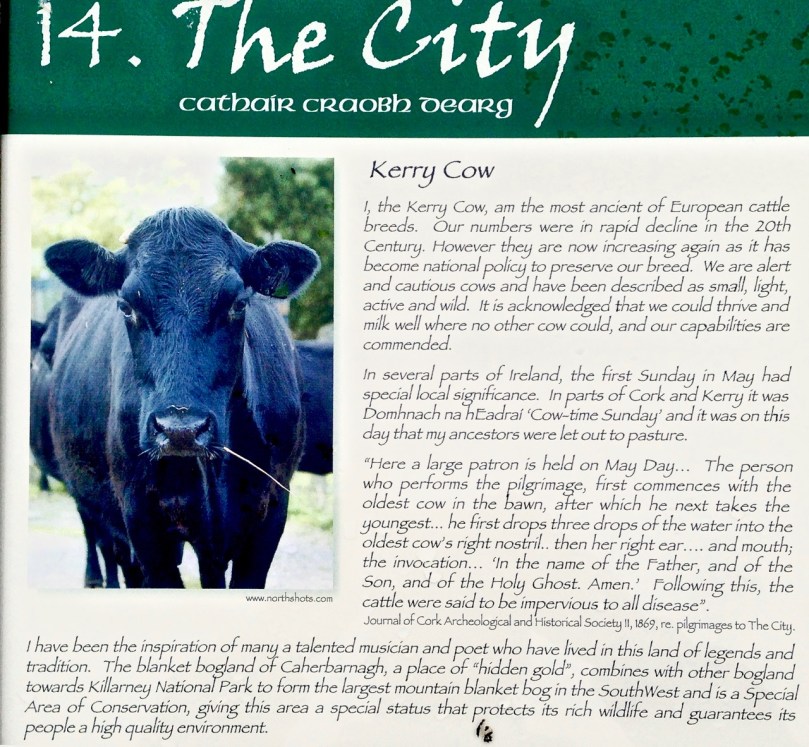

One interesting custom was the driving of cattle and horses into the water. This is mentioned in the 1680s by Piers in his Description of the County of West-Meath: …On the first Sunday in harvest, viz in August, they will be sure to drive their cattle into some pool or river, and therein swim them; this they observe as inviolable as if it were a point of religion, for they think no beast will live the whole year thro’ unless they be thus drenched; I deny not but that swimming of the cattle, and chiefly in this season of the year, is healthful unto them…