…down the rushy glen – we daren’t go a-hunting for fear of little men! We were hunting mountains last week when we travelled up the west coast of Ireland with a visiting friend – finding some of the best scenery this country has to offer.

If you look down on the island from above (as in this view from NASA, below) the lie of the land is very clear: the high points are all around the perimeters, yellow and brown in colour, with lower green plains in the centre.

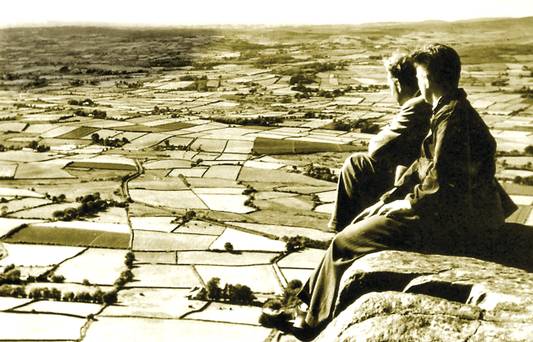

If you lived in a country like Canada, then Ireland’s mountains should seem like mere gentle slopes. Our highest peak is not too far from us, up in Kerry, Carrauntoohil (Irish: Corrán Tuathail – this could mean Tuathal’s sickle or fang, Tuathal having been a common Irish name in medieval times) and this is only 1038 metres to the summit. However, the overriding characteristic of Irish mountains is that they often sweep steeply down to the sea or to a lough and are therefore visually spectacular in their settings.

If you lived in a country like Canada, then Ireland’s mountains should seem like mere gentle slopes. Our highest peak is not too far from us, up in Kerry, Carrauntoohil (Irish: Corrán Tuathail – this could mean Tuathal’s sickle or fang, Tuathal having been a common Irish name in medieval times) and this is only 1038 metres to the summit. However, the overriding characteristic of Irish mountains is that they often sweep steeply down to the sea or to a lough and are therefore visually spectacular in their settings.

We live in the far south-west: our mountains form the backbone of each of the peninsulas: The Mizen, Sheep’s Head, Beara, Iveragh and Dingle, largely Old Red Sandstone with some Carboniferous Limestone north of Killarney. Our travels took us up to Clare – very distinctive exposed limestone ‘pavements’ and mountain tops – and then to the complexities of granite, schists and gneisses found in the district of Connemara.

The four pictures above show the elements of the landscape in Connemara, Co Galway: quiet boreens, reflective water and dramatic mountains

The Irish landscape -and, particularly, her mountains – has long been the inspiration for artists and poets. The work of Paul Henry (1877 – 1958) is sparse and flat, yet expertly captures the character of the high lands of the west. It has been used over and over again in tourist advertising campaigns.

Paul Henry’s work was part of popular culture during his lifetime (above): now his art is very collectible and can be found in international galleries (below)

Killary Harbour, Connemara (above) and in Paul Henry’s landscape (above left) is said to be Ireland’s only true fjord (a flooded valley cut by glacial erosion which outlets to the sea): in the foreground are mussel ropes

We stayed in the Lough Inagh Lodge – a comfortable hotel with great character and superb views to the mountains. There I was pleased to discover two original oil paintings by Leon O’Kennedy (1900 – 1979), a little known artist who travelled mainly in the west of Ireland and, evidently, sold his work by knocking on doors. The hotel’s paintings might have arrived in this way as they depict local views: the prism shaped peat stacks are still very much in evidence in Connemara.

Connemara (which derives from Conmhaicne Mara meaning: descendants of Con Mhac, of the sea) is partly in County Galway and partly in County Mayo, in the province of Connacht. We were there only two days and barely did it justice. We intend to return and get to know it more intimately. In terms of our tour of Ireland’s mountainous districts it was the icing on the cake, but that in no way lessens the particular beauty of the other places we encountered – the strangely haunting limestone heights of Clare and the perennial grandeur of Killarney: all are experiences not to be missed.

Limestone landscape in the Burren, Clare (top) and the lakes of Killarney, Kerry (above)

…By the craggy hillside,

Through the mosses bare,

They have planted thorn-trees,

For pleasure here and there.

Is any man so daring

As dig them up in spite,

He shall find their sharpest thorns

In his bed at night.

Up the airy mountain,

Down the rushy glen,

We daren’t go a-hunting

For fear of little men.

Wee folk, good folk,

Trooping all together;

Green jacket, red cap,

And white owl’s feather!