I was out of the country when the writer, Peter Somerville-Large, died in October – I just realised this week that he is gone. What another loss to the world of Irish culture and writing. I never met Peter, but we exchanged letters in the aftermath of me publishing the post I wrote in 2014 and which I reproduce below – a review of his most beloved book, The Coast of West Cork. The book is still in print, although the newer paperback editions lack the black and white photographs of the original.

Here’s an example, and it’s one that shows why this book is such an important record of its time, the early 1970s. According to Mindat, The Coosheen Copper Mine was. . .

Once dubbed the “richest mine in the world” by a correspondent with the London Times, . . . worked a small but extremely rich copper deposit close to the surface from 1839-1877. The mine briefly reopened in 1888-1890 and again in 1906-1907 but only produced a trivial amount of ore. . . On the top of the hill 5 fenced off shafts can be seen and the largely obliterated ruins of the engine house built in August 1860 (bulldozed by the local council in the 1980’s as it was deemed both dangerous and an eyesore!).

This photograph of Ballydehob reminds us what a thriving commercial town it was. 55 years later, you can still recognise the shopfronts, although few are actively trading.

The final photograph from the original edition of the book that I want to share is of a temperance meeting in Skibbereen. Do any of our readers remember this?

And now, here is the original post, written 11 years ago, 1n 2014

The Coast of West Cork

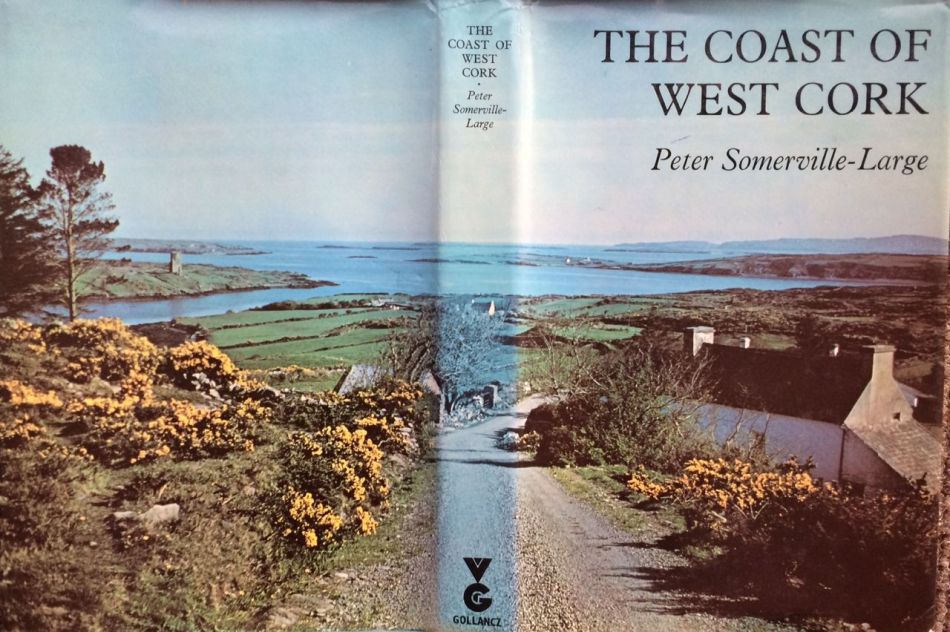

Every personal library in West Cork, maybe in Ireland, has a copy of the book The Coast of West Cork by Peter Somerville-Large. First published in 1972, it is a classic of travel writing – amusing, learned, thoughtful – that still holds up as a fascinating portrayal of this part of the world. The photograph above is of the front cover of the book, signed by the author, that I brought with me to Canada when I emigrated in 1974. Forty years later, I am living on the very spot where this photograph was taken! It took me a while to figure this out, as the picture is actually reversed. [EDIT: note that when this photograph was taken, in 1970, the castle was still intact – most of it collapsed in a storm in 1974. For what it looks like now, see Robert’s 2020 post, The Castle of Rossbrin.]

Peter Somerville-Large, now in his 80s, is still writing. He is connected to the old Castletownshend families (Edith Somerville was a relation and he mentions Townsend aunts) and was already very familiar with West Cork when he set out to tour it by bicycle in the spring of 1970. He takes every road, every byway and boreen, and describes in detail the scenery, the characters and the conditions along the way.

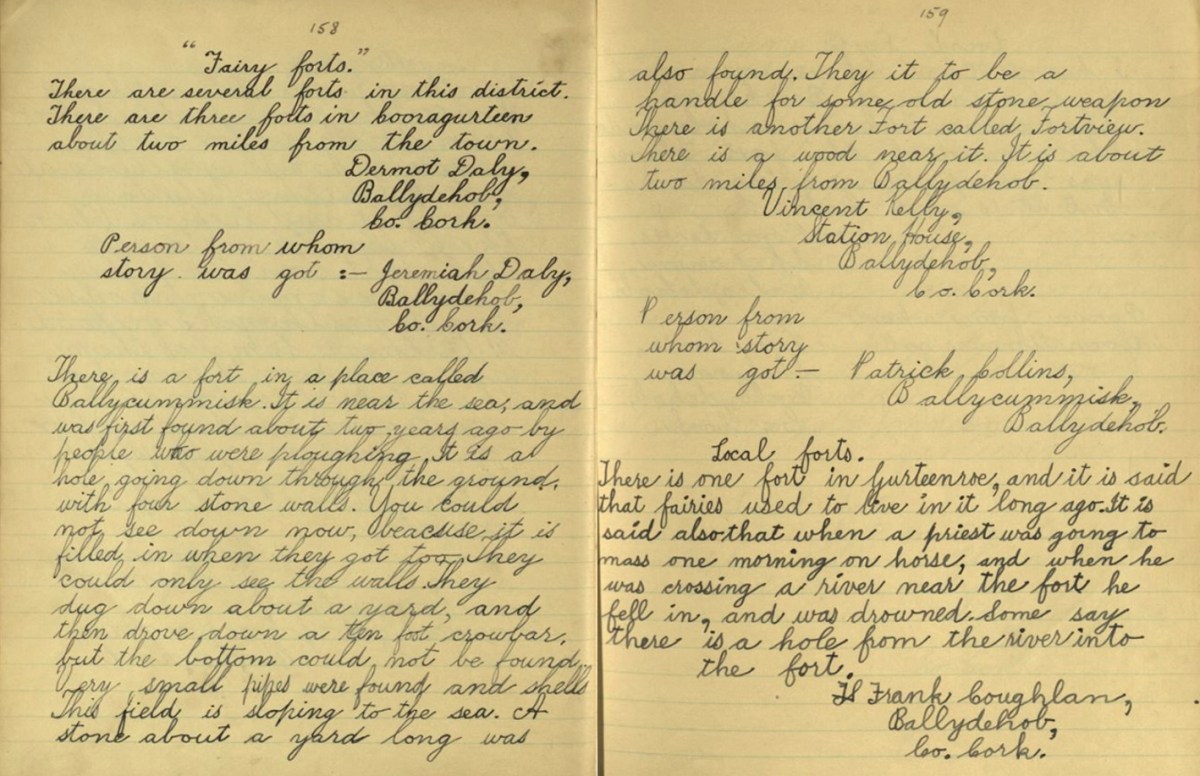

Far more than a travel diary, this is a comprehensive account of West Cork. Somerville-Large’s erudition is impressive. Either before or after his journey he spent many hours in the National Library, researching the history, folklore, archaeology and literature of the area and he weaves this knowledge seamlessly into his narrative. Because of his own personal background, he is able to include stories and anecdotes from the Big Houses of the gentry. A great aunt

…remembered going down to a cellar which was filled with swords used to arm the tenants during the time of the Whiteboys and also with empty stone wine jars which had carried wine smuggled in from France. From this cellar there was believed to be a passage underground to the O’Driscoll Castle of Rincolisky, whose truncated remains are to be found in a neighbouring field…An earlier Townsend sent his…page down the passage to see if it was clear. The boy was never seen again.

His affection for the place leads him to mourn the loss of population from the Islands of Roaringwater Bay.

One by one the small islands became deserted…Only a few years ago I visited Horse Island, just opposite Ballydehob. The last people there, an elderly couple, were living all alone. It was summer, and the old man was sitting in a chair outside his house, his feet in a basin of water. His wife, behind him, fed hens. Next year, they were gone. The house, still intact and comfortable, stood empty, the linoleum in place, last year’s calendar on the wall. Down by the pier a plough had been thrown into the water where it looked like a gesture of despair.

He documents the importance of the creamery in the social life of the townlands, the old occupations of fishing and mining and the loss of such sources of income, the string of castles that dot the coast and the great irish families that built them, the brash new bungalows springing up around the scenic areas, the awful legacy of the famine, and the sheer beauty of the scenery. He is conscious of a way of life passing. Going out of his way to visit a sweathouse (a feature of the Irish countryside in times past) he ends up in the O’Sullivan’s kitchen, drinking whiskey and eating biscuits.

Mrs. Sullivan told me that the valley was once thickly populated, and when she was a girl there had been sixty children at the school that closed last year. The way of life had gone with it…Once it had been a great place to live in, her husband said. There were monthly fairs at Ballydehob and Schull, and he had walked all the way to Bantry with the cattle and all the way back again.

The parts I have quoted deal with the area around where we live, but the bicycle trip stretches from Clonakilty to the Beara Peninsula. Describing West Cork as it was in 1970, it is now an important historical document in its own right, alongside such accounts as Thackery’s Irish Sketchbook of 1879, or the Pacata Hibernia of 1633. Mostly, however, it is a charming, engaging and fascinating depiction of a special place.