We were on the trail of Saint Brendan, and the road took us deep into County Kerry. The spring days were blue, and the unparalleled scenery at its best for us. As we made our ways through the high hills and mountain passes we could see across to the coast:

20,000 years ago, ice shaped the Kerry landscape: a huge glacier flowed from here towards the sea. Looking down from An Chonair, the highest mountain pass on the Wild Atlantic Way; the peak in the centre is Mount Brandon, named for Saint Brendan. The header picture shows the burial ground and, beyond, the medieval “Brendan’s House’ at Kilmalkedar, seen through the burgeoning spring growth

Our first call was to the Cathedral in Ardfert, which was built in medieval times over a Christian monastic site founded by the Saint in the sixth century. There’s nothing left of that, but the later buildings, while ruined, are well looked after by the Office of Public Works, and an information centre is open through the summer months – certainly worth a visit.

Seen in Ardfert Cathedral, an image of a woodcut dating from 1479: it shows St Brendan and his monks on their epic voyage in search of Paradise. On the way, they discovered the American continent!

We could not miss a visit to the place of the Saint’s birth in 484 – Fenit, near Tralee – where a monumental bronze sculpture was installed in 2004. It was made by Tighe O Donoghue/Ross of Glenflesk.

It’s hard to do photographic justice to Tighe O Donoghue/Ross of Glenflesk’s sculpture of Saint Brendan in Fenit: he’s depicted as a ‘warrior saint’ (in the same vein as St Fanahan – or St Fionnchú – of Mitchelstown, Co Cork). Certainly he has a heroic character, necessary for someone who embarked on (and returned from) so many adventures

The culmination of our Brendan travels for this trip (there’s so much more yet to be explored) was the medieval site at Kilmalkedar, on the Dingle Peninsula. This monastic settlement is rich in history, and includes St Brendan’s House, and St Brendan’s Oratory. These alone are spectacular monuments, but there are further riches to delight the eye of Irish history enthusiasts. Finola’s post this week concentrates on the wonders of Irish Romanesque architecture, and the ancient stone-roofed church at Kilmalkedar is a prime example.

The wonderful Romanesque early Christian church at Kilmalkedar – right – with ‘Brendan’s House’ in the distance. The site is overflowing with medieval history. Below. the setting for the monastic site is stunningly beautiful. Note the large, very ancient cross and the holed ogham stone

A good while ago – in 1845, in fact – our excursion was foreshadowed by Mary Jane Fisher Leadbeater, who writes in her Letters from the Kingdom of Kerry:

…Our object to-day was not entirely to pay homage to Nature, though in the heart of her lovely works, but to visit the ruins of the wonderful church of Kilmelkedar, which we were solemnly assured “was built in one night by holy angels.” One evening, ever so many many ages ago, the sun, when he set in those wilds, saw no place dedicated to the worship of the Creator: he rose the following morning, and smiled upon a perfect chapel, with pillared niche and carved saint, and a holy fount, and massy cross! all ready for the purposes of prayer and sacrifice! A matin-call rang loud and clear over lofty mountain and lonely glen, to summon the devout and arouse the unthinking, where no vesper strain could sound the evening before; all gleamed proud and fair in the glad light, and the heart of man became purified, as the sacred bell called him to prayer! And this was the reward of the unceasing prayers of the holy Saint Brandon! Such is the legend…

St Brendan’s House – behind a locked and barbed gate!

We spent hours at the Kilmalkedar site and didn’t take everything in. We consider ourselves so privileged: we had it completely to ourselves, and the day was perfect. Saint Brendan treated us very kindly – except that his ‘House’ and an associated holy well were not accessible: although an OPW project which has recently undergone significant restoration, the enclosure around it is impenetrable with barbed wire and a firmly locked gate. However, in an adjacent field, a gate and path gave us free access to a large, flat stone which seemed to be covered in giant cup-marks. The National Monuments register describes it as a ‘Ballaun Stone’: it’s very fine, and I was delighted to find that Mary Jane Fisher Leadbeater had unearthed some folklore about it:

…This place contained a colony of monks; and well they knew what they were about when they fixed on this retirement; for, besides its real advantages, it commands a most lovely view of Smerwick Harbour, The Sisters, and Sybil Head. They need not want for fish in the refectory in the days of abstinence. It is situated in a sheltered recess of the mountains, fine springs around, and, another popular legend bearing witness, in the centre of what was once good grazing and tillage ground. A cow is the subject of this legend—a cow of size and breed suited to provide milk for the giant race of those days. We saw the milk vessels, and if she filled them morning and evening, she was indeed a marvellous cow. In a huge flat rock were these milk pans; six large round holes, regular in their distances from each other, and nearly of equal size; they could each contain some gallons of liquid. This said cow gave sufficient milk for one whole parish; and was the property of a widow—her only wealth. Another parish and another clan desired to be possessed of this prize; so a marauder, endued with superior strength and courage, drove her off one moonlight night. The widow followed wailing, and he jeered her and cursed her as he proceeded. The cow suddenly stopped; in vain the thief strove to drive her on; she could neither go on, nor yet return; she stuck fast. At length, aroused by the widow’s cries, her neighbours arrived, and the delinquent endeavoured to escape. In vain—for he too stuck fast in the opposite rock; he was taken and killed. The cow then returned to her own home, and continued to contribute her share towards making the parish like Canaan, “a land flowing with milk and honey.” The prints of her hoofs, where the bees made their nests, are still to be seen in one rock ; and those of the marauder’s foot and hand in another, where he was held fast by a stronger bond than that of conscience…

Kilmalkedar’s giant ballaun – the cups were filled every day by the widow’s marvellous cow, providing milk for St Brendan’s community of monks back in the day

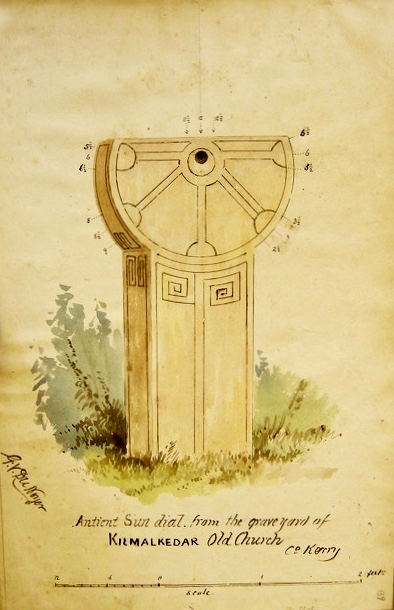

One of the special features of the Kilmalkedar site harks back to its medieval monastic associations – a sundial. The ordered lives of the monks were regulated by divisions of the day (and night) – the Canonical Hours, also known as the Divine Office or Liturgy of the Hours. These were the regular periods of prayer: seven daytime Offices of Lauds (at daybreak), Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, Compline (at sunset) and a night Office of Vigils. This was the important work of the monastery, of course: constant and regular prayers. In between it the monks had to fit in all the requirements of daily life: sustenance, growing crops, brewing, beekeeping. And, on top of all that, Brendan and his companions undertook their peregrinatio all around the known world. No wonder a timepiece was necessary!

The Kilmalkedar sundial is a particularly elegant example – it’s probably my favourite item on this site: functional and beautiful, as all things wrought by the human hand should be. In such an evocative environment it certainly helps us to cast our minds back to the life and times of the travelling Saint. The antiquarian George Du Noyer visited the place back in the 1860s, and was also drawn to this particular artefact, accurately recording it for us in one of his exquisite watercolour sketches.