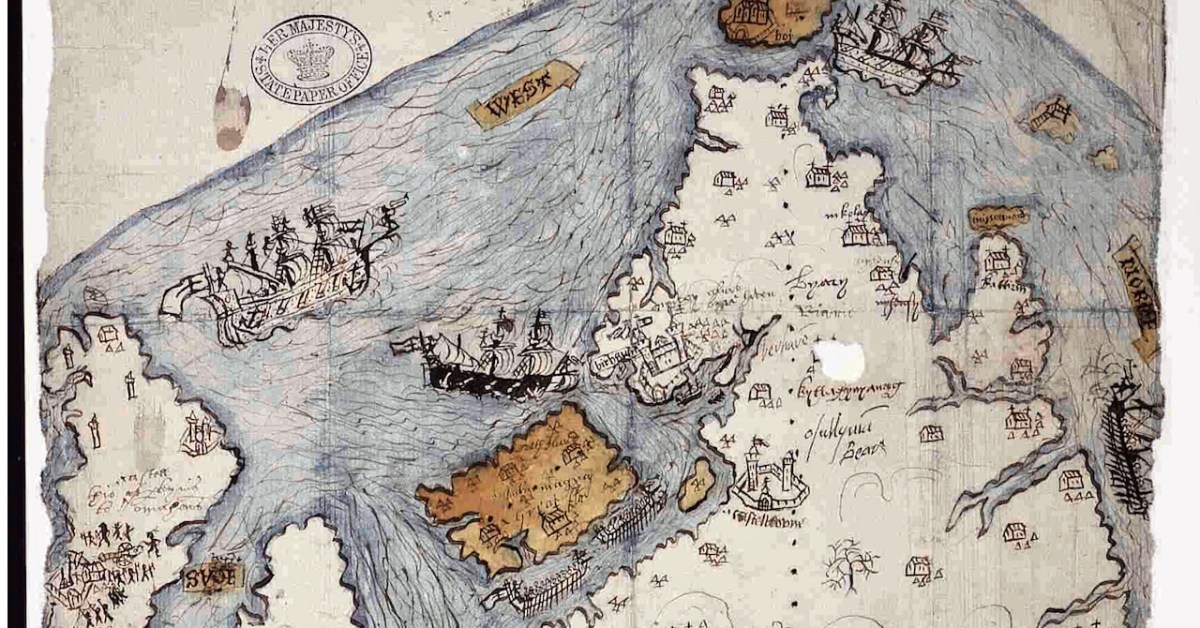

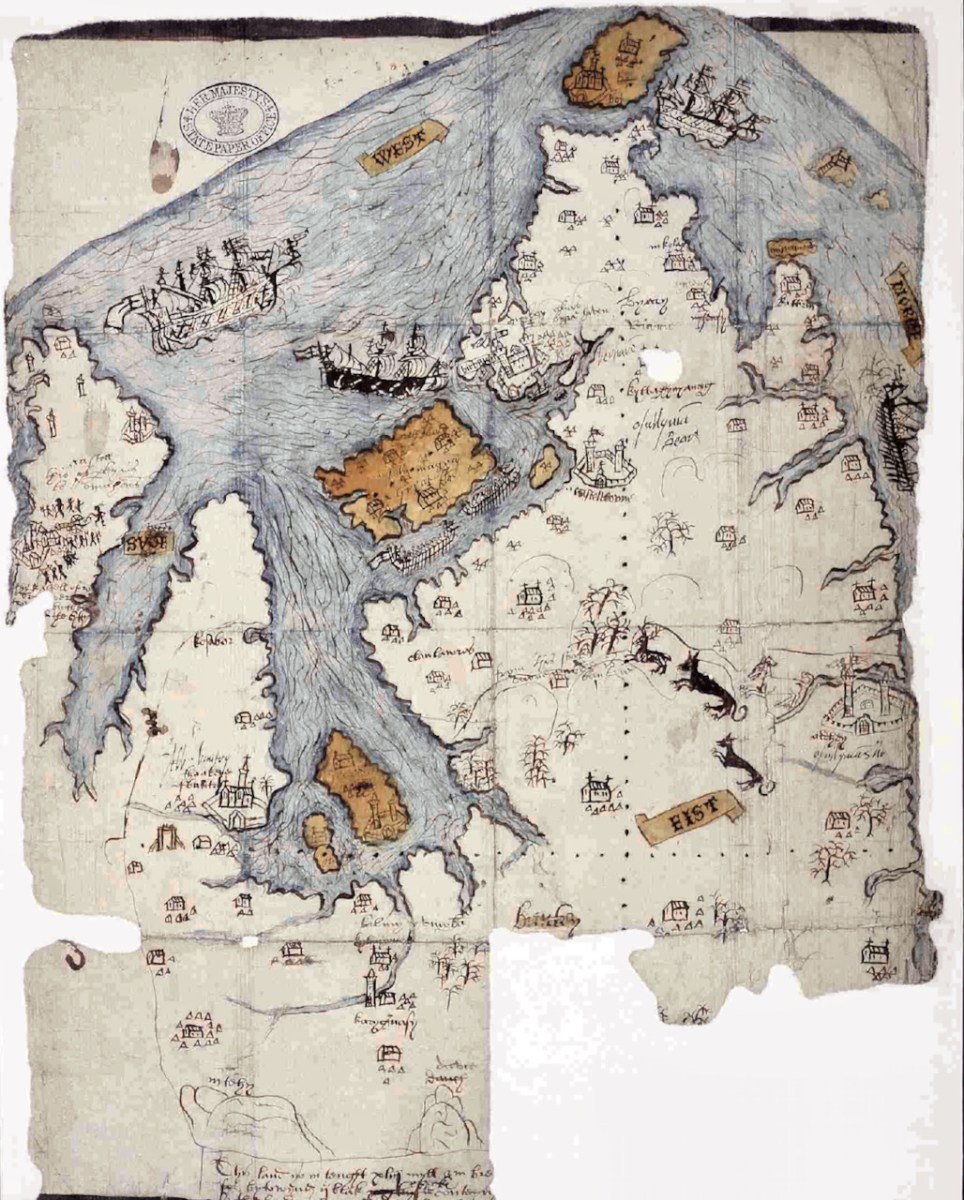

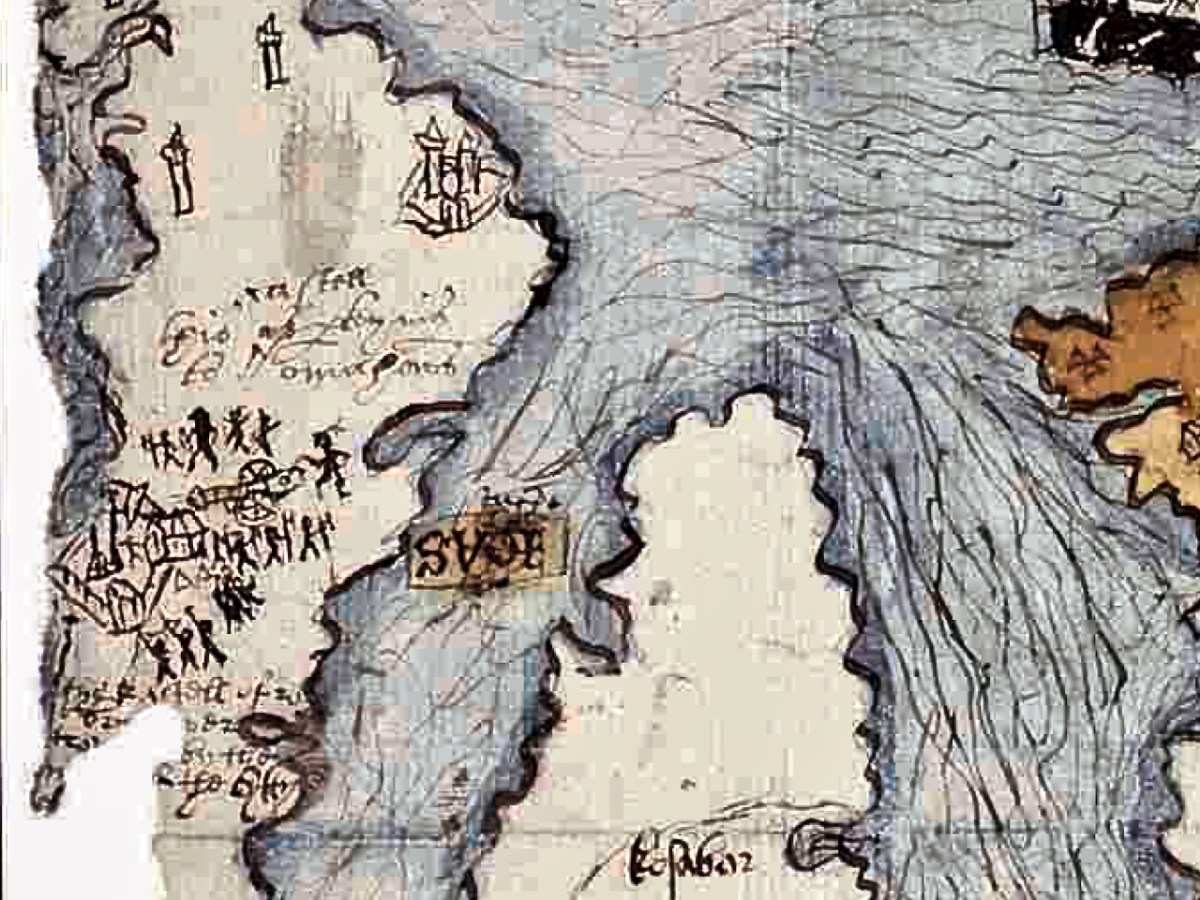

The Elizabethans were map-makers, especially if they needed information for the purpose of wars and conquests. I was first alerted to this extraordinary map of West Cork by a reference in the O’Mahony Journal (subscription needed) and then to a piece written on it for the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society in 1958 by P O’Keeffe who labelled it a Map of Beare and Bantry. Neither of these sources had a good image of the map and so, intrigued, I sent off a request for a digital copy to the British National Archives. It arrived by return email, at no charge. What a service! (Irish national repositories take note.) Here is the complete map.

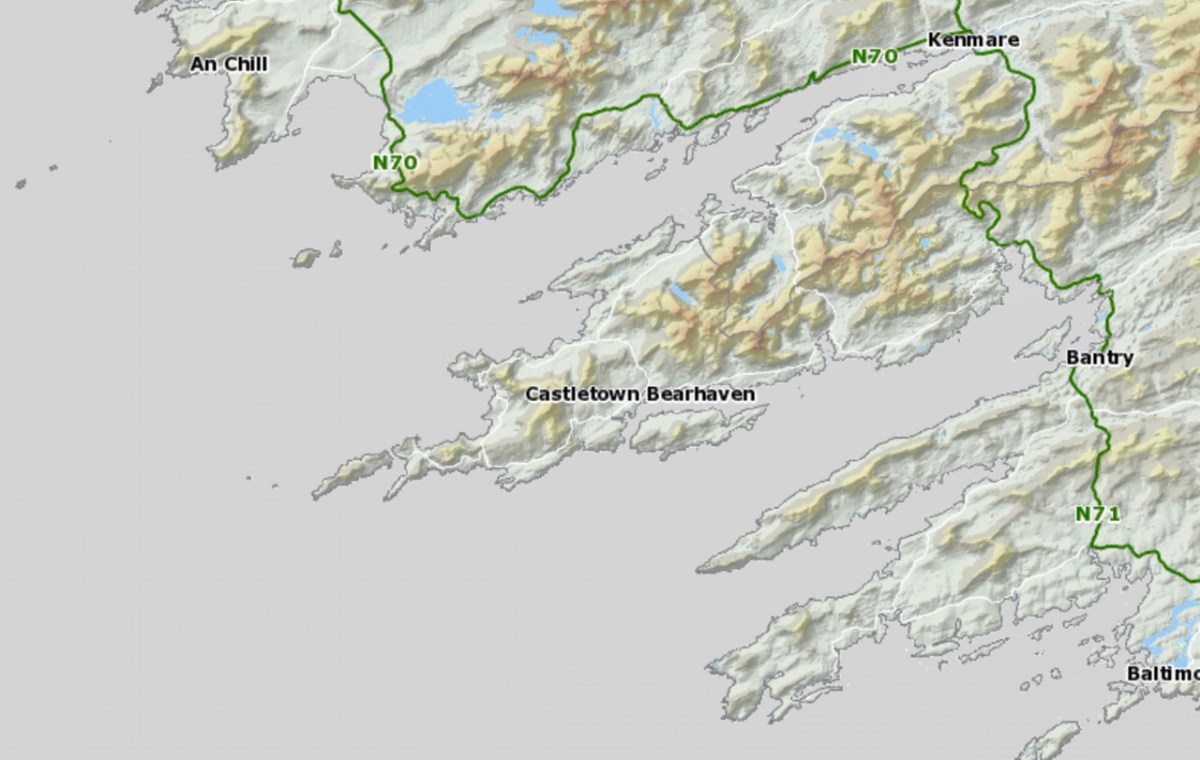

While it is clear that this map dates to the Elizabethan period, there are many questions about it: who did it, for what purpose, exactly when? For this post I want to go through elements of the map and identify, as far as possible, what it depicts. A subsequent post will deal with what is actually going on – that is, what are the actions that are being chronicled. Let’s start with the fact that the map is quite accurate. It depicts the three peninsulas of West Cork – the Mizen, the Sheep’s Head and the Beara – and the inlets in between them. It is oriented east-west rather than our modern convention of north-south, but the cardinal points are clearly identified. The map is drawn on paper, with the sea coloured in blue and the islands in brown. I have provided maps below of the same area, the first in our typical north-south orientation and the second as it is orientated in the historical map.

The sea is shown teeming with ships – warships and galleys. Taking a closer look at the two north of Bear Island we see two different ships, one light and one dark. Each is in full sail, with men on the riggings and in the look-outs. They have cannons emerging from the hull, a trumpeter aft and a bugler on the bow-spit.

As a reference, here is a painting by Andries van Aervelt showing the kinds of ships that were engaged in The Battle of the Narrow Seas (1585) – both the full-sail warships are shown as well as galleys.

Galleys were also deployed here, shown between Bear Island and the mainland (below). The lead galley has a trumpeter on the bow, while the second galley shows a man blowing a horn in the stern and what looks like a drummer on the bow (like those ramming speed scenes in Ben Hur). The rowers were often convicts and the life of a galley rower was brutal. This map shows a single row of oars. Galleys essentially provided platforms upon which armed soldiers could shoot, and had the advantage of being more stable than sailing ships and often faster, depending on wind and swell.

Another warship (below) is rounding the tip of the Beara , heading for Dursey Sound. Dursey Island has both a church and a castle on it. There isn’t much trace of this now, but there was an O’Sullivan castle on a small grassy peninsula on Dursey, described as two rectangular buildings with a rectangular enclosure in the National Monuments records. It was destroyed in 1602 (more about that in the next post) along with what was then left of the church, known as Kilmichael, which was already in a ruinous state. At the right, in this section of the map, are two rocky islands, one with a set of steps leading up to a church. Could this be Skellig Michael? The other candidate is Scariff Island, off Lamb’s Head, which had a monastic settlement and hermit’s cell on it.

Let’s take a look now at the area around Bantry (below). The large church is of course the Franciscan Abbey that stood here, where the graveyard is located There is a church shown on the aptly-named Chapel Island between the mainland and Whiddy (no trace if it now remains), and both a church and a castle on Whiddy.

The fragmentary remans of an ecclesiastical enclosure can still be seen at the graveyard on Whiddy, while the O’Sullivan Castle has only one wall still partly standing. That’s it, below.

The hinterland of the Beara is shown with trees and animals. Either this is a hunting scene with dogs chasing a stag, or it is meant to show the wildness of the interior, with wolves and deer. Settlements are indicated by churches surrounded by a cluster of cabins (not that different from Irish villages up until recently), and there is a castle labelled Ardhey and O Sulyvans Ho. This is likely to be the ruined casted of Ardea, which actually stands on the other side of the Kenmare River – the Iveragh side rather than the Beara side.

The final depiction I want to highlight is of the Mizen. Several towers dot the landscape as well as two substantial castles, one of which is under siege.

Which castles are these – especially the one being attacked? Tune in next week!