This post was inspired by a gift from my oldest and dearest friend – three books on stained glass passed on to me because he is moving from his home of the last 65 years, a home in which I spent much happy time. A loyal reader of our blog, he knows of my enthusiasm for stained glass, an obsession I shared with his late wife, the wonderful Vera, whom I still carry in my heart.

One of the books is the exhaustive and erudite study of Harry Clarke by Nicola Gordon Bowe. The other two are more general, although each of them devotes a section to the work of Harry Clarke. My initial intention was to look at Harry Clarke as a illustrator, with special reference to his portraiture, using a variety of windows as examples. I may still do that in the future. However, I’ve decided that for now, just one window perfectly illuminates what I want to say about Harry Clarke this time. It’s a window we have both used before in posts (Robert in his Martinmas piece, and I in a couple of places) – the Kendal Coghill window from St Barrahane’s in Castletownshend. Through this window I hope to show you the unique genius of Harry Clare, but also how he drew from life and from great art to create his stained glass panels. (For more on Harry Clarke’s life, see my previous post, The Nativity – by Harry Clarke.)

Who was Kendal Coghill? He was born and bred in Castletownshend, Edith Somerville’s uncle and a distinguished soldier, rising to the rank of Colonel. He served in India, where he took a kindly and active interest in the young Irish soldiers in his regiment. One of his melancholy duties was writing to their mothers to advise of their deaths. He was also “excitable and flamboyant”, writes Gifford Lewis in her excellent book, Somerville and Ross: The World of the Irish R.M.. As one of the leaders of the amateur spiritualist movement in Castletownshend he introduced Edith and her brother Cameron to automatic writing. By all accounts he was generous and warm hearted and it was his compassion that the window was to emphasise. The two subjects were chosen carefully – Saint King Louis IX of France, and St Martin of Tours. Coghill could trace his ancestry to King Louis, famed for his beneficence, and St Martin was the patron saint of soldiers.

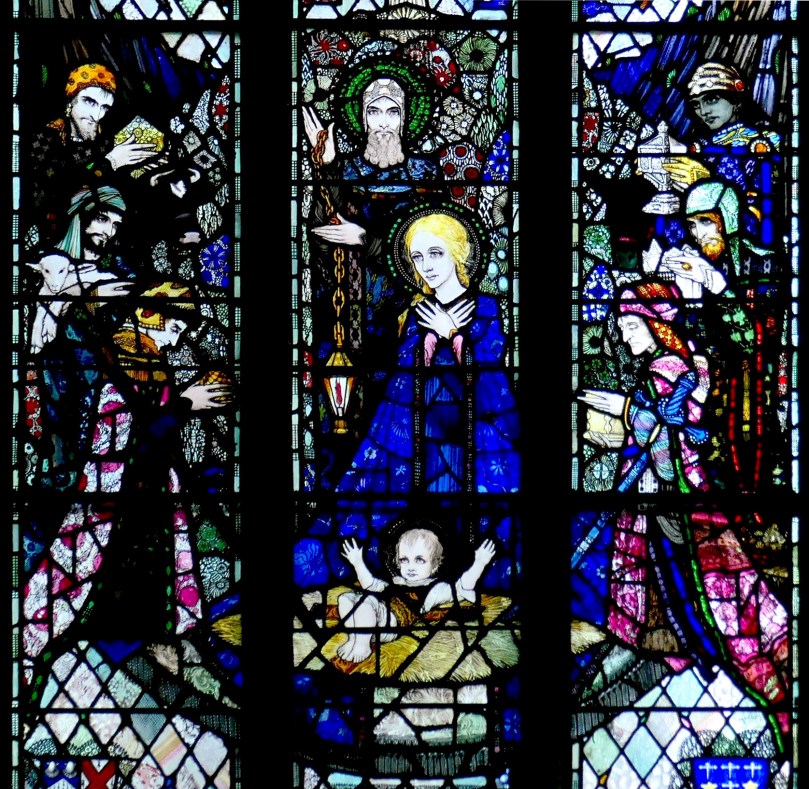

The first thing that strikes you upon entering St Barrahane’s is the contrast between this window and the others (by Powells of London) on the south side. Alongside the conventional Powells the Clarke blazes with colour and with detail. Every square inch is individually worked, there are no repeated patterns or conventional scrolls. Examine the borders, for example, filled with abstract and colourful motifs, never recurring.

St Louis detail: each motif in the border is uniquely designed and coloured. The robe intrudes in front of the border, lending a 3D effect

Harry’s habit of placing figures at different heights adds visual interest to the side-by-side panels and may have been influenced by Japanese pillar prints, which were also a major factor in the design aesthetic of Frank Lloyd Wright. A church window is by its very nature long and narrow and the design challenge this poses had first been explored by Japanese artists whose woodblock prints were hung vertically on walls, or fixed to house posts. Contrast the static, forward-facing, identically scaled figures in the Powell window with the dynamic composition of the Clarke panels. The St Martin figure, in particular contains two figures and manages to tell a whole story, like this example of a pillar print.

Harry’s habit of placing figures at different heights adds visual interest to the side-by-side panels and may have been influenced by Japanese pillar prints, which were also a major factor in the design aesthetic of Frank Lloyd Wright. A church window is by its very nature long and narrow and the design challenge this poses had first been explored by Japanese artists whose woodblock prints were hung vertically on walls, or fixed to house posts. Contrast the static, forward-facing, identically scaled figures in the Powell window with the dynamic composition of the Clarke panels. The St Martin figure, in particular contains two figures and manages to tell a whole story, like this example of a pillar print.

The choice of the window and the management of the commission rested with Edith Somerville. Harry Clarke stayed with her in Drishane while executing the final placement and she liked him very much. Beside the Kendall Coghill window which is the subject of this post there are two other Clarke windows in St Barrahane’s. But St Barrahane’s, as Gifford Lewis explains, is not…”typically Protestant. High Church, Anglo-Catholic influence is in restrained evidence besides the astounding blaze of Clarke’s windows. Jem Barlow, the medium, claimed that at a service one Sunday in St Barrahane’s the spirit figure of Aunt Sidney appeared, caught sight of the Clarke windows, started, then exclaimed “Romish!” and dissolved.”

Saint Louis occupies the left panel. He is depicted with an alms purse in his left hand and a crucifix instead of a sceptre in his right hand. Look carefully – above him are the poor and sick that were the objects of his constant charity. Here’s what Nicola Gordon Bowe has to say about this section of the window:

Dimly visible…is a small procession of the heads and shoulders of the poor and diseased who used to feed at his table. These again show Harry’s unique ability to depict the gruesome, macabre and palsied in an exquisite manner…The seven men depicted, old, bereft, angry or leprous, are painted on shades of sea-greens and blues, mauves and grey-greens, in fine detail with strong lines and a few brilliant touches, like the grotesque green man’s profiled head capped in fiery ruby, the leper helmeted in clear turquoise with silver carbuncles, and the aged cripple on the right in ruby and gold chequers.

This section, it seems was likely influenced by a painting that Harry was familiar with from visits to the National Gallery in London – Pieter Bruegel’s Adoration of the Kings.

The ship in which he sailed to the crusades is depicted above King Louis.

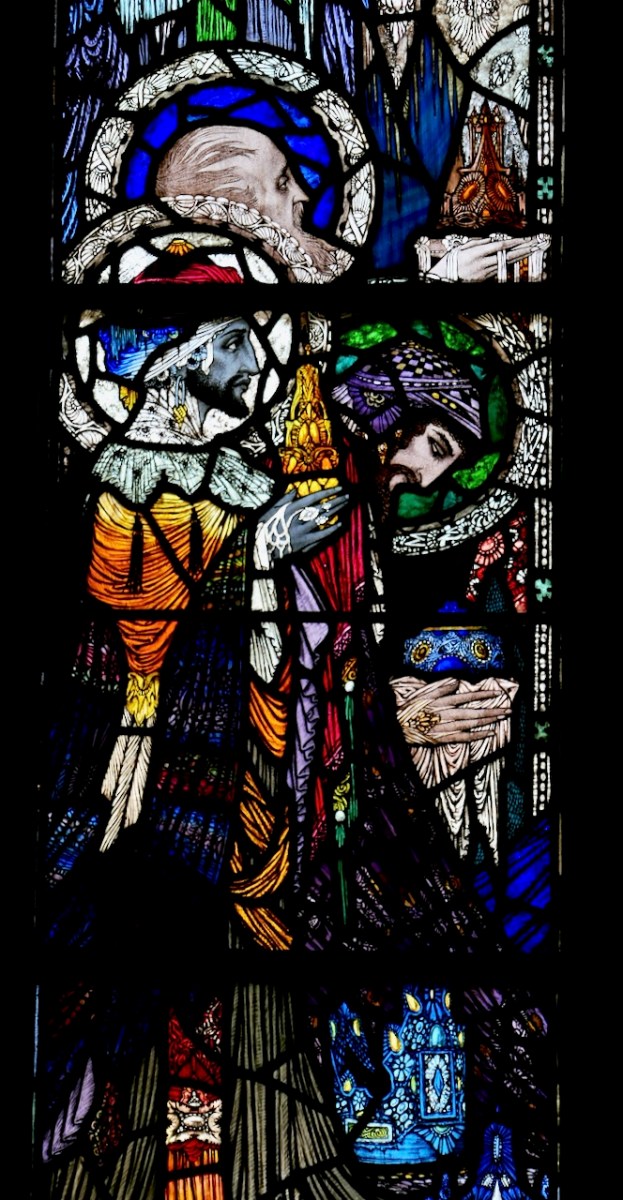

Saint Martin, in the right panel, is depicted in the act of cutting his cloak in two, to give half to a beggar. Martin’s face is archetypal Clarke – the beard, the aquiline nose, and the large eyes filled with compassion for the beggar.

The helmet is worth a closer look. First of all, it is beautifully and finely decorated in the niello style, and second, it is topped with a tiny figure, sphinx-like, with long wings. Nicola Gordon Bowe points to the influence of Burne-Jones here, to the helmet worn by Perseus in The Doom Fulfilled.

Clarke also found his inspiration in life drawing. He used himself for a model occasionally, but also ordinary people from the streets of Dublin. The beggar may have been based on one familiar to him. His face is dignified despite his wretched condition and his patches are rendered in as exquisite detail as is the Saint’s armour.

Finally, at the very top of the window two haloed figures look down. Harry Clarke had a thing for red hair and this is a perfect example of how he used that preference to good effect. Once again, although the figures are similar in size, there is no repetition – these are no ‘standard’ angels – each has his own wonderful garments and stance.

Stained glass artists typically sketch their designs on paper first and these images are referred to as cartoons. Harry Clarke’s cartoons for the Coghill windows must still exist. Nicola Gordon Bowe describes them as drawn “loosely in thick charcoal, the design boldly expressed with detailing and shading minimal, but still conveying a good idea of how every part of the window would look.” The finished window, she says, “reveals a new freedom of treatment, the painting on the glass reflecting the free drawing of the cartoons.” This is an artist and craftsman working at the height of his powers – an interesting subject for the question that Robert poses in his post this week.