It’s time to move inside! Now that you are all experts in tower house construction from the outside, let’s go into one of these small castles and see how they were built.

Remember that a tower house was all about defence and thus many of the features you will find inside have much to do with an expectation of attack and little to do with comfort. This was all fine, of course, as long as weapons consisted of bows and arrows, swords and spears, and even muskets. But as soon as cannon appeared on the scene the tower house was doomed – even its thick stone walls were no proof against such a bombardment.

Ironically, having a wall or two blown away by cannons, as at Raheen Castle (by Cromwellian forces), above, allows us to see the internal construction of the castle. In the case of Raheen the lower floors were separated from the upper floor by an enormous barrel-vaulted ceiling.

Dunlough Castle – note the projecting corbel denoting a wooden floor, and the imprint of the wicker scaffolding on the ceiling mortar

These vaulted ceilings were wicker-centered. A scaffolding of wicker was erected first and a layer of mortar laid on top of that. Ceiling stones were laid on the scaffold and mortared into place and then the stone work was built up to provide the floor of the next story. When the scaffold was dismantled the impression of the wicker was left on the mortar – clearly visible in several of our examples here.

The entrance was often a raised entrance (see When is a Castle..?) with access via an outside wooden stairs that could be pulled up when necessary. Tower houses where the entrance was on the ground floor needed a defended access and this was often in the form of a small lobby, externally (as at Dunlough Castle) or internally, as at Kilcrea Castle. The door was secured with a heavy wooden bar, slotted into a bar-hole.

At Kilcrea we see that the lobby could be defended from each side and also from above, with the addition of a murder hole – literally a hole through with the inhabitants could throw rocks or boiling water down on those trapped in the entry.

Each floor was accessed by a stairway. Although some very basic castles may have relied on internal wooden stairs leading from one floor to another, most staircases were accommodated inside the walls – thus they are called mural stairs.

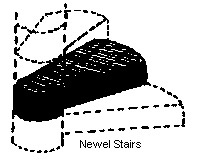

Stairs were both straight or spiral and some castles had both. A straight set of stairs didn’t need a very thick wall, but a spiral stairs needed either very thick walls or a corner tower or projection. Building a set of spiral stairs was a highly-skilled task and not just because of the inherent difficulty of working with intractable stone.

They were usually built so that you ascended them clockwise, thus presenting more of yourself to defenders above, who could hold onto the newel post with their left hand and wield a sword in their right. It was important to make the steps slightly uneven too, so that an ascending attacker could trip easily if he didn’t watch carefully.

Windows had to be inserted to light the way but these could only be slits, to be used as arrow or gun loops when necessary. A cross-shaped loop was called a crosslet.

This crosslet provides light for a spiral staircase and allows a defender to shoot from inside the castle

One of the most beautiful examples of a spiral staircase we have come across is at Kilcrea Castle, near Aherla in Cork. While all such staircases* are impressive, the one at Kilcrea is a work of art. All the wall and sill stones are dressed to conform to the shape of the spiral and the sinuous progression of the newel and the steps is a joy to behold.

One of the most beautiful examples of a spiral staircase we have come across is at Kilcrea Castle, near Aherla in Cork. While all such staircases* are impressive, the one at Kilcrea is a work of art. All the wall and sill stones are dressed to conform to the shape of the spiral and the sinuous progression of the newel and the steps is a joy to behold.

The beautifully constructed spiral staircase at Kilcrea Castle. All the stones are dressed to fit the contours of the circular stairwell

The walls hold other items of interest too. Mural chambers, for example, may have served a variety of purposes from storage to dressing – some have loops for lighting but many have not. Cupboards were built into the walls to hold lights and valuables – a mural cupboard is called an aumbry.

Two mural chambers: left is a rectangular chamber with two aumbries (cupboards) and right is an L-shaped chamber light by a loop

Garderobes (indoor toilets) are usually enclosed in a mural chamber for privacy (although not always!), with the garderobe chute extending down the wall to an external exit.

Upper: The garderobe at Ballinacarriga. Lower: Dunmanus Castle showing where the garderobe chute exits at the base of the castle

The lowest floor was often used for storage or for cattle and hence the floor was sometimes left in a natural state.

The next floors were for administration and daily living activities of castle inhabitants and workers. Floors were wooden – corbels and beam sockets to support the floors show where the next level began.

Cullohill Castle – floor levels clearly visible, plus the addition of a later fireplace that obscures a window

Fenestration (the arrangement of windows) was organised to emphasise defence – small windows and loops on the lower floors, larger on the top floor or solar. This was the private living quarters of the lord and his family, and a place where the women of the household could enjoy privacy and peace.

It was sometimes the only room in the castle to have a fireplace and generally speaking was the most comfortable room and therefore also used for entertaining.

Top floor, Kilcrea – the only floor with sizeable windows and more finely finished than the lower floors

If this floor had more than one room, the other might be called the great hall and be the entertainment space.

Ballinacarriga is unique in West Cork in that there are several carved window embrasures.

From the solar a stairway led to the battlements and wall walk. The roof could be made of timber, slate, or even thatch. The wall walk at Kilcrea had specially designed weepers to carry water away from the roof.

So there you are – next time you wander around a deserted castle in Ireland (we specialise in them!) you will be able to rattle off the proper terms for everything you see. The more you know, the more you appreciate the genius of our Medieval castle-builders.

I’ve learned so much doing these posts on castle architecture I am tempted to move on to abbeys – what do you think?

* The illustration of the newel stairs is from the Castles of Britain website. I believe it is from an Irish castle. That site also has an excellent glossary.