The second set of stories about Mount Gabriel (the first set was Legends of Mount Gabriel: The Bottomless Lake) also relate to physical features on the landscape and how they came to be there. Most involve the prowess and deeds of giants, including Fionn MacCumhaill/Finn McCool. Fionn MacCumhaill was the mythical hero/warrior of the Fenian Cycle, a set of stories dating back to the seventh century and added to during the whole of the Early and Later Medieval periods. The stories tell of his boyhood, how he acquired the gift of knowledge, his pursuit of the beautiful Gráinne and her lover Diarmuid, his son Oscar and Oscar’s son, Oisin. Fionn, you must know, is not dead – he merely sleeps and will awake again when somebody sounds his hunting horn, to defend Ireland during her hour of greatest need.

This image depicts a man stumbling upon the sleeping Fianna in a Donegal cave. It is by Beatrice Elvery and is one of her illustrations for Heroes of the Dawn by Violet Russell, 1914, available at archive.org

But somehow, in popular folklore Fionn, the mighty hero of the ancient sagas, transformed into the giant, Finn McCool, a genial leviathan capable of feats of prodigious strength. All over Ireland places are named for this enormous figure (e.g. Seefin – Finn’s Seat, is the name of several mountains) and tales are handed down about his effect on the landscape. Perhaps the most well-know story is about the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim, but there is hardly a spot in Ireland that doesn’t have similar stories. Mount Gabriel is no exception.

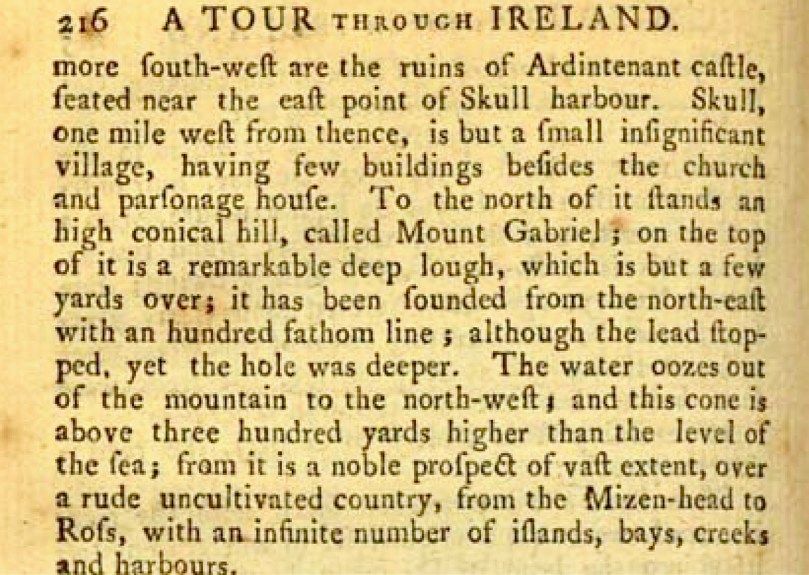

A distant view of the Fastnet Rock and Lighthouse

We’ve already seen one of those stories in The Bottomless Lake in which Fionn took a handful of rock and threw it out into the Atlantic Ocean where it is now as the Fastnet Rock or Carraig Aonair – leaving the hole of Poll an Oighin. That story was from the pen of an unidentified student in the long-abandoned school of Gloun. The student spells it Glaun, it’s identified as Gleann in the School’s Collection and as Glan on OS maps and it’s usually given locally as Gloun. The school is pictured below as it looks now.

The student had more stories about Fionn, arising from the geological formation of Mount Gabriel.

The name of the townland in which I live, and in the which this school is situated, is Glaun. It is in the parish of Schull about three miles from the village in the county of Cork, in the Barony of West Carbery. It is bounded on the north by the Glaun river, on the east by Mount Gabriel, on the south by “Fionn’s Ridge” and on the west by the Lios a Catha river. . .

Fionn’s Ridge separates Glaun from Gubbeen. It is a ridge of rock with seams resembling the furrows made by a plough and it is said that Fionn Mac Cumhail ploughed it with two rams and a wooden plough. Of course it is only a story as the surface was torn off by masses of ice moving south to the hollow below leaving the rock bare like a ridge.

A variation on this story is given by another student, also unnamed, in Schull.

Fionn Mac Cumhaill’s Ridge

There is a curious formation of rock at the western side of Mount Gabriel. It resembles a furrow ploughed into the rock. It is called Fionn’s Ridge. The people of the locality say that it was Fionn Mac Cumhaill ploughed this furrow with two goats.

When we moved here first we met local electrician and theatre scholar, Ger Minihane. At the time we were trying to track down a cup-marked stone in the townland of Derreennatra and having no luck. But Ger told us where to find it – in his own garden! And he told us the legend of how it got there, thrown from the top of Mount Gabriel by Fionn MacCumhaill, a story passed down through the generations in his family.

Was this the coat hook of the anonymous student at Gloun School?

While many of the stories of rocks hurled from Mount Gabriel (more on those another time) refer generically to the actions of ‘giants’, local people understand that it was Fionn MacCumhaill himself that was doing the hurling and his name has become strongly associated with the mountain. During the Millennium celebrations a group in Schull took on the task of creating colourful street theatre to honour those legends and we are fortunate that a record remains of what must have been the most fun, engaging and dramatic events ever to happen in Schull – including the image used as my lead photograph of Fionn striding through Schull*. This movie documents the planning and effort that went into The Battle of Murrahin, which pitted the O’Mahony clan against their ancient rivals, the O’Driscolls. Towards the end of the video we meet up with Fionn.

The story that is told in this re-enactment is the local one that the Fastnet rock originated when Fionn threw a rock from Mount Gabriel into the sea, where it settled and became An Carraig Aonair, The Lone Rock. However, the group’s research also showed up an old Irish name for it which translates as ‘The Swan of the Jet-black cairn bereft of light in the dark’ and this explains the appearance of the black swan.

Related to the idea of the Fastnet as a swan is this local legend from a Schull student.

There is an old story told among the people about it. It is said that when St Patrick was banishing Paganism out of Ireland the devil was in such a rage that he pulled a piece of rock out of Mount Gabriel and flung it into the Atlantic ocean some miles west of Cape Clear. This lone rock had been many years there and several ships were wrecked on it until close on one hundred years ago a big lighthouse was built on it. This rock was called the Fastnet rock and the lighthouse got the same name. In Irish it is called Carraig Aonair. This lighthouse is situated on one of the greatest trade routes in the world..

It is said that on every May morning the Fastnet Rock leaves its place and sails around Cape Clear and northwards to three rocks called the Bull, Cow and Calf, and returns to the place again before sun-rise.

*Thanks so much to Karen Minihan for providing images and links from SULT Schull, the Millennium projects. Wish I’d been there!