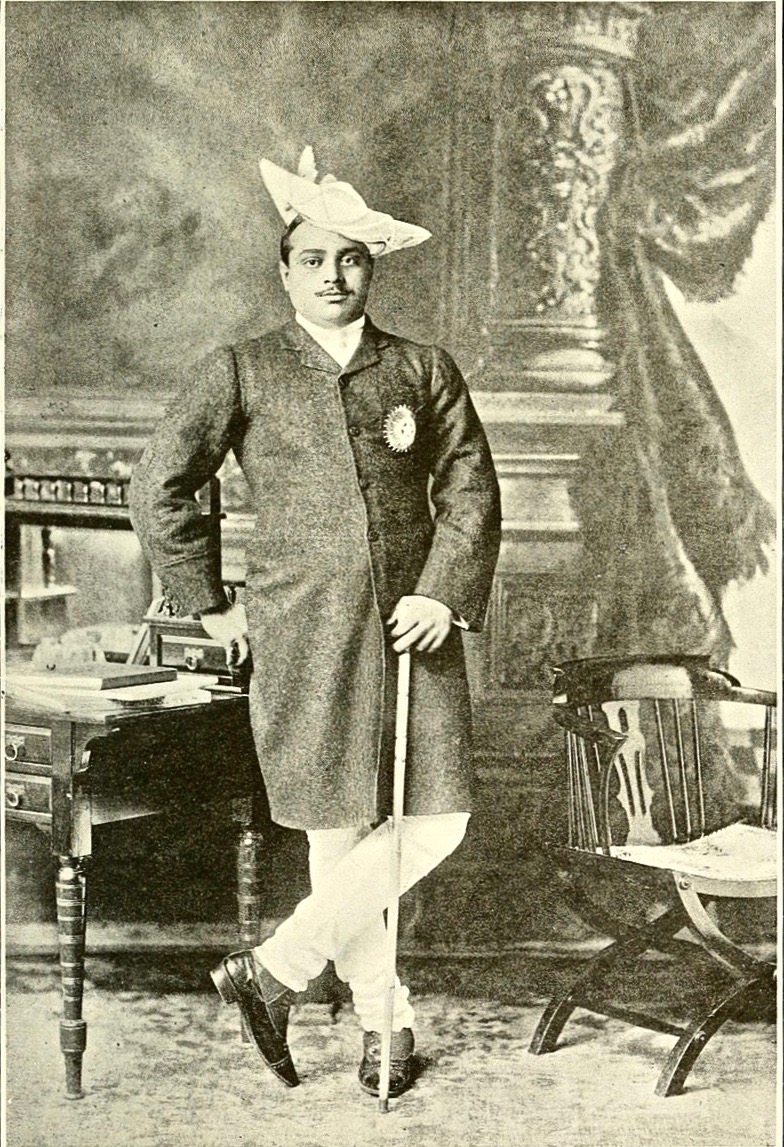

The more I look into the Church of the Ascension in Timoleague the more fascinating it becomes. Last week I concentrated on the mosaics and the story of the Maharaja, but what I failed to say is that the mosaic tiles were made by Minton, as were the encaustic tiles on the floor. Minton is known for its bone china but in fact it was also was the leading producer of British ceramic tiles during the 19th century.

The encaustic floor tiles as well as all the mosaic tiles were made by Minton

The windows were also produced by the most famous British stained glass artists of their day, as we shall see. Taken as a whole then, the architecture and decoration of this singular church leads us directly to Augustus Pugin, one of the giants of the Victorian Age, and locates it in the highest echelons of the Gothic Revival Movement. This hidden gem is even more of a jewel than I suspected!

Who was Augustus Pugin? Born in 1812, son of a French emigré draughtsman and an English mother, Pugin trained in his father’s workshop, becoming proficient in design and drafting by aged 9. Conversion to Catholicism and a visit to Nuremberg in Germany convinced him that the greatest expression of church architecture was High Gothic and he set about challenging, and ultimately revolutionising, the prevailing design norms of the Victorian period. He was incredibly prolific and influential, such that today when we think about Victorian architecture and gothic revival, we are really thinking about the work of Augustus Pugin – even though he died in 1852 at the early age of 40.

The signature of the Warrington Stained Glass Company on the East Window

Pugin designed several churches in Ireland (mostly Catholic), especially in Wexford, where you can follow the ‘Pugin Trail’. (I don’t know who wrote the Wexford Pugin Trail brochure, but it is one of the best explanations of his style and influence that I have read.) While he did NOT design the Church of the Ascension, his influence is everywhere in evidence, along with the use of his favourite suppliers – Minton for the mosaics and tilework and Warrington, Lavers and Westlake, and Mayer for the windows.

Hallmarks of gothic revival: a beautiful hammer-beam ceiling, tall pointed windows with simple Y tracery, everything to lead the eye upwards

The real art of making stained glass in the medieval style had been lost and during the 18th century colour was mostly painted directly on the glass using an enamel technique. But part of the gothic revival ethic was to base manufacturing technology as closely as possible on the original so there was also a re-discovering of real stained glass processes where the colour was fired directly into the material and sections of glass were separated by lead. This art was revived in the 19th century by artists and craftspeople who studied medieval glass and learned through trial and error how to make it again.

The Presentation, East Window

Let’s start with the East Window, the work of Warrington. William Warrington was one of the leading stained glass artists of his day. Like Pugin, he was a student of the gothic style and he strove to reproduce glass work as close as possible to medieval models. He had trained with his father as a painter of armorial shields, an influence that can be seen in his designs. He wrote a book in 1848 on The History of Stained Glass, but fell afoul of the group called the Cambridge Camden Society (or CCS) who had set themselves up as the arbiters of taste in all things related to church architecture. Partly this was the outcome of class prejudice: the CCS, all university educated men, did not believe that a “mere artisan” should be allowed to have an opinion of what they saw as their own exclusive preserve.

Detail from The Raising of Dorcas, East Window

By any standards, this is a beautifully executed window. According to the Wikipedia article, Warrington’s figurative painting strives towards the Medieval in its forms, which are somewhat elongated and elegant, with simply-painted drapery falling in deep folds in such a way that line and movement is emphasised in the pictorial composition. His painting of the details, particularly of faces, is both masterly and exquisite.

The Raising of Dorcas, East Window. In this story, from the Acts of the Apostles, Peter prays over the dead body of Dorcas, who returns to life

This is all clearly visible in the East Window, a masterful set of three lights depicting the Crucifixion in the centre, Raising Dorcas on the left and the Presentation in the Temple on the right. Note the use of heraldic motifs above the main panels, and the tall medieval-style spires of foliage, all typical of Warrington glass.

For some reason, this was all too much for the Bishop of Cloyne when he came to consecrate the new chancel in 1861. Cloyne Cathedral itself was a true medieval building but much simpler in its interior decoration. The Bishop obviously had less sympathy with this new style of highly decorated church interiors and objected in particular to the East window, which he viewed as similar to the ‘graven images’ popular in the Catholic churches.

He refused to conduct the consecration unless the window was covered in a cloth. The cloth, apparently stayed up a long time, and when it came down the window continued to attract opprobrium – it was even attacked and broken on at least one occasion! It’s hard to understand now how such a beautiful piece of devotional art could have inspired such an over-the-top reaction.

The Sermon on the Mount by Lavers and Westlake

Three sets of windows in the nave are by Lavers and Westlake, yet another of the London-based stained glass firms that responded to the new demand for gothic-revival glass windows in 19th century Britain. Nathaniel Westlake was another scholar of stained glass, publishing a four volume work, A History of Design in Painted Glass, and also a decorative painter of wall and ceiling panels. He was considered one of the leading exponents of stained glass art with a style considered to be Pre-Raphaelite. He worked with William Burges for a while – the one who designed every aspect of St Fin Barre’s Cathedral in Cork – who recommended him to the firm of Lavers and Barraud. In 1868 he became their chief designer and was responsible for much of the success of the firm, which captured a large share of the booming stained glass industry. Unlike Warrington, however, Westlake did not clash with the CCS, probably because his partner, Lavers, was a member of that society.

A detail from the Lavers and Westlake Loaves and Fishes window showing Westlake’s Pre-Raphaelite tendencies

The three windows by Lavers and Westlake are in the nave on the north and south walls. Those on the north wall depicts the Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes and the Sermon on the Mount. That on the south wall is of Jesus Walking on the Water.

Above, detail from the Loaves and Fishes. Below, Jesus Walking on the Water

Above, detail from the Loaves and Fishes. Below, Jesus Walking on the Water

The final window on the south wall is by the firm of Mayer and the subject is The Good Centurion. Franz Mayer and Co was possibly the busiest stained glass company of all and are actually still in business under the name Mayer of Munich. The founder, Franz Mayer, started a company dedicated to “…a combination of fine arts, architecture, sculpture and painting…”. This firm was officially recognised by the Vatican so it was very popular with Catholic churches and there are many examples of Mayer windows throughout Ireland. In 1865 the firm opened a London branch, which supplied this window.

The Good Centurion, a window by Mayer of Munich and London

There are three more windows in the south transept, these ones by the firm of Clayton and Bell. They are very fine indeed and I particularly like the east and west window pair which depict, apparently, Life and Death, for their wonderful luminous colours.

Clayton and Bell windows, detail

There are several more noteworthy features of this fine little church (the pulpit, the carved wooden furniture) but I think I will leave it at that for now. I’ve learned a lot about the Gothic Revival Movement through this exercise, and about some of its chief practitioners. I’ve been struck, as the reader might be, at how British (rather than Irish) the influences are in this church, but that of course was very much a function of the times. At some point I will write about the enormous Catholic church that dominates the village, with a view to showing how the great era of Catholic church building in Ireland finally led to an emphasis on Irish architecture and Irish artisans. For a very brief word on that, you can read my post A Tale of Four Churches.

Timoleague. On the left are the ruins of the medieval friary, the Catholic Church dominates the hilltop, and the Church of the Ascension is behind the green building on the far right

And as for Augustus Wellby Northmore Pugin – you can learn more about this complex genius through the BBC Program Pugin: God’s Own Architect, available on YouTube.

Email link is under 'more' button.

Scarrif and Deenish are the two islands out from Derrynane Bay. Uninhabited for 40 years, they are the site of salmon farms now. We walked down Lamb’s Head to get a better view of them.

Scarrif and Deenish are the two islands out from Derrynane Bay. Uninhabited for 40 years, they are the site of salmon farms now. We walked down Lamb’s Head to get a better view of them.