Four years ago I wrote about the fishing industry that once flourished on the shores of Roaringwater Bay (and around much of the west coast of Ireland): according to extant records it was active before 1500, and probably had its heyday in the seventeenth century, when it was heavily invested in by the Great Earl of Cork (Richard Boyle, sometimes described as ‘the richest man in the known world’). In those days, pilchards were the main catch: huge shoals of them came to the comparatively warm, sheltered waters of the islands during the summer months, along with other oily fish such as herring and mackerel. Seine boats were commonly used for this enterprise. Today, pilchards are rare: through a combination of overfishing and changing climate, the bountiful shoals no longer appear.

Header – pilchard curing in St Ives, Cornwall c1890: the pilchards are piled up in layers, forming the huge mound in the centre of the photograph. They are salted and weighted down. Above – curing the fish, Valencia Island, Co Kerry, early 20th century (Reddit / Ireland)

Shooting the Seine:

There were two boats per seine net, the seine and the faller. The seine boat was 27 foot long with a beam close to nine foot. The golden rule on the Northside was to never get into a boat whose beam was less than one third its length. The seine boat had five oars of about 17 foot (bow, Béal-tuile, aft, bloc and tiller oars). The crew of seven had to shoot the seine net; one man shooting the trip rope, another to feed out the bunt rope, four men rowing and the huer (master of the seine and captain of the boat) directing the operation. The faller (or bloc) boat was 24 foot long with a crew of five. Its job was stoning and to carry any fish caught. The largest load a faller could carry would be around 5,000 fish. All boats carried a Crucifix and a bottle of Holy Water.

(from Northside of the Mizen by Patrick McCarthy & Richard Hawkes, 1991)

Twentieth century remains of a seine boat, from Northside of the Mizen

If the fish are gone, remains of the machinery of that industry are still to be seen. In particular, the sites of some of the curing stations – or Fish Palaces – are visible, and are recorded on the National Monuments Archaeological Survey Database. Take a look at the map below: I have drawn green pilchards to show the sites of fish palaces mentioned in the database – eleven in all on this section of the map. Also shown by red pilchards, however, are the sites of another six ‘curing stations’: these are mentioned in a long article by historian Arthur E J Went, Pilchards in the South of Ireland, published in the Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society in 1949: Volume 51, pages 137 – 157.

Known sites – or historical mention of – fish palaces (curing stations) in the South West of Ireland (information from National Monuments database and Arthur E J Went, Pilchards in the South of Ireland 1949)

The active fishing of pilchards on a large scale in Ireland has been discontinued for many years so that, unlike Cornwall, there is little left, apart from published records, to indicate its former importance. There is, however, published information as to the methods of fishing, and a few sites of old curing stations, frequently called pallices, can still be identified.

from Arthur E J Went, Pilchards in the South of Ireland, 1949

Arthur Edward James Went (1910–80), noted fisheries biologist and historian, lived at Sandycove, Co Dublin. In 1936 he was appointed Assistant Inspector of Fisheries in the Department of Agriculture, Dublin, and later was promoted to the position of Scientific Adviser and Chief Inspector of Fisheries

As explorers of all things historic and archaeological – particularly in West Cork – Finola and I couldn’t resist visiting some of the sites of Palaces – or Pallices – documented in these studies. We have always know about the one nearest to Nead an Iolair, in Rossbrin Cove – it’s just down the road: a perfect sheltered harbour, although it does dry out at very low tides. However, there seems to be some debate about exactly where this one is located. It would date from the time of William Hull and the Great Earl of Cork, so how much would be left after 500 years? There is a field on the north shore of the Cove with an old name: The Palleashes which, according to Arthur Went (quoting local tradition), was the site of a curing station for pilchards, operated by the ‘Spaniards’. There seems to be some difference of opinion locally as to which of the many small fields here is the actual site, although it is likely to be close to the large, now modernised quay, as this shows up on the earliest maps.

In the upper picture: the quay at Rossbrin is still used by small fishing boats today. Centre – the field above the present quay may be The Palleashes, and therefore could be the site of the medieval fish palace: there are very overgrown signs of stone walls here. Lower picture – the old 6″ OS map, surveyed around 1840, shows a lane accessing the area above the quay (to the left of the ‘Holy Well’ – that lane is no longer there today) and there are buildings close to the shore which could indicate the palace. In 1840 there was no road running along the north shore of the Cove, but the strand at low tide would have been used as a thoroughfare. Just above the ‘Holy Well’ indicated on the shoreline – and slightly to the right – is a small red dot. This is the area shown by Arthur Went as the possible site of the fish palace (and subsequently marked as such on the Archaeological Database); in my opinion it is more likely to have been directly accessed from the water.

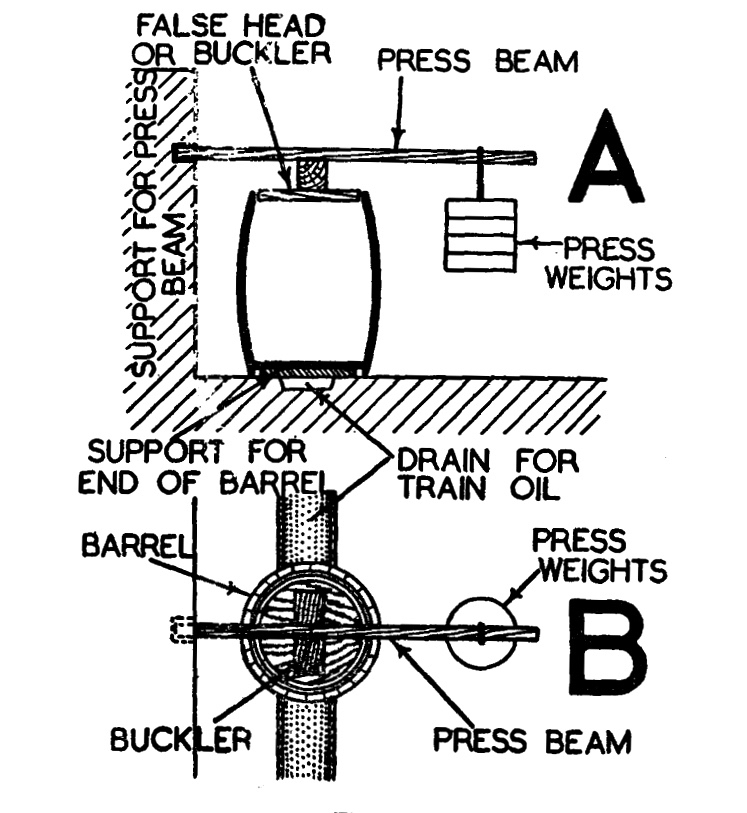

A sure sign of the site of a fish palace is a line of perforations or holes – as can be seen above at Baltimore, where a substantial curing station is recorded (although it may only date from the nineteenth century). Large timbers were inserted horizontally into these holes to form a ‘press beam’ to provide leverage for bucklers to squash out the oil from the salted pilchards, as shown in Arthur Went’s diagram, below:

The ‘Train Oil’ – produced from the compressed pilchards – was a valuable commodity, and was collected to be stored and used for treating leather, and as fuel for lamps. As a by-product of the pilchard industry it was said to be as valuable as the fish themselves.

Palace Strand, in Schull

To continue my researches I went along to Schull, where Arthur Went mentions a ‘Palace House’ on ‘Palace Strand’ – an inlet just to the east of the main harbour. This is right beside the old railway station which was not quite the terminus of the Schull & Skibbereen Railway, as a spur went on from the station to serve the harbour itself. The station buildings and part of the platform are still there – now a private residence. I could not find anything in the area shown on Went’s map at the east end of the strand, but I did find something at the west end.

In the upper picture is a wall on the western boundary of the old station site in Schull. This contains beam holes very similar in size and spacing to those we have seen in fish palaces elsewhere: it’s very tempting to think that this wall – now part of a derelict building – may have had this purpose, as it is well situated close to the shoreline of Palace Strand. If this was a fish palace, it is also likely to date from the nineteenth century, as the early Ordnance Survey maps don’t indicate it. The centre picture shows the old station buildings today, and the lower picture taken at Schull Station in 1939 reminds us of past times: the railway closed in 1947.

This post is a ‘taster’ for a fully illustrated talk I’m giving at Bank House, Ballydehob, on Tuesday 26 February at 8pm: Pilchards & Palaces – 300 years of Fishing in South-West Ireland. It’s part of the Autumn series of Ballydehob’s ‘Talks at the Vaults’