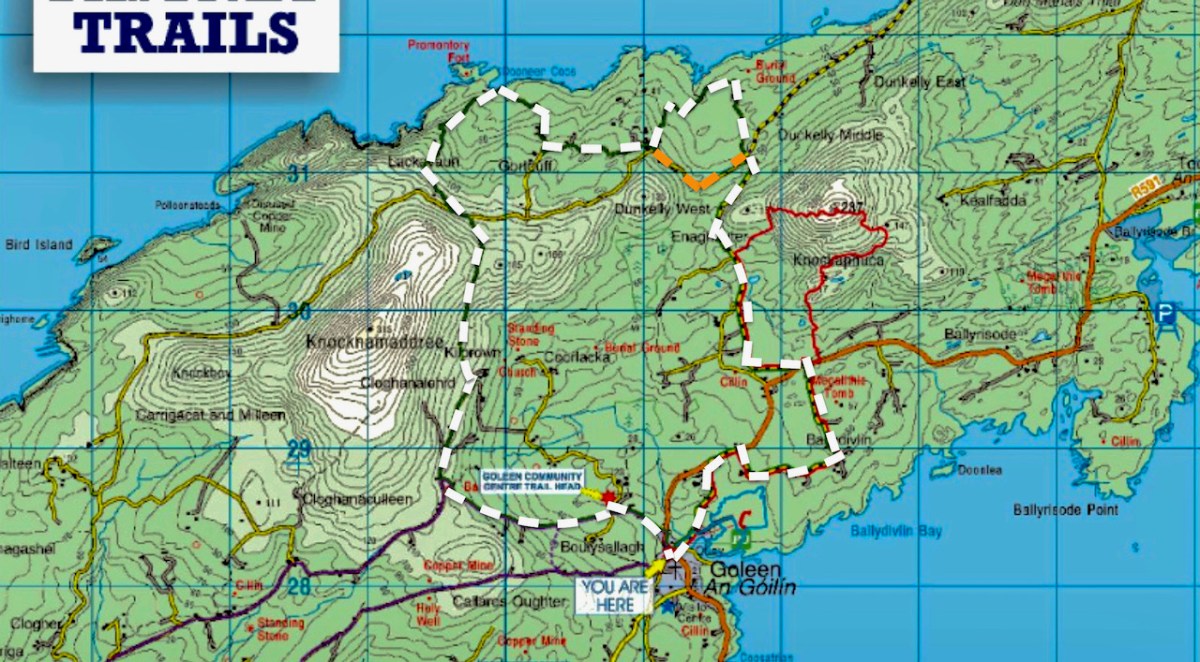

The Cliffs of Dooneen – surely that’s in Clare? Well, no, the song was actually written by Jack McAuliffe about the cliffs near Lixnaw, Co Kerry, from which Clare can, apparently, be seen. It was initially popularised by Paddy Breen, a traditional flute player, but got famous when it was performed by Christy Moore of Planxty. Paddy Reilly has a nice version too. But the Dooneen we are talking about today is the one on the Sheep’s Head, a few kilometres beyond Kilcrohane and on the way-marked trails of the Sheeps Head Way. It’s a spectacular spot, well worth visiting for no reason at all other than to contemplate the glories of the scenery in this part of the world.

Dunmanus Castle can be glimpsed across Dunmanus Bay (above), and the whole of the Mizen Peninsula lies across from you, from Mount Gabriel to the end of the Peninsular where Dunlough Head hosts the magnificent Three Castles.

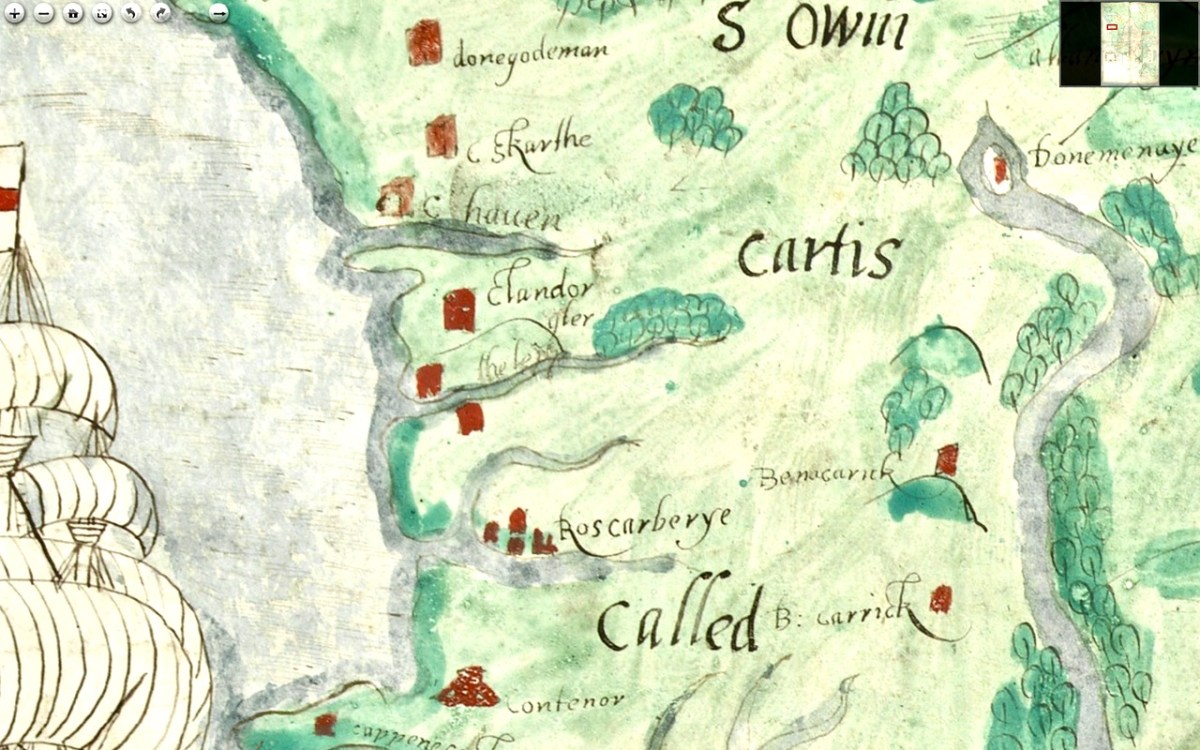

Dooneen (Dúnín – ‘Little Fort’) has been a locus of activity for a long time, probably because it provides a sheltered spot for boats. Sheltered – but not necessarily safe!

The pier here is substantial. This was the centre for a busy fishing industry early in the 20th century. We’ve often talked about the 15th century as a time when vast shoals of pilchards and herring congregated in the waters of West Cork. It happened again in the first half of the 1900s, and this is when this pier probably dates to. We know that, because it is not shown on the 6” or 25” Ordnance Survey Maps which date from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

There are a couple of buildings that may relate to the processing of the fish (see Robert’s post Pilchards and Palaces for an explanation). And this odd feature below – what looks like a holding pond created by a concrete dam.

An excellent page on eOceanic provides directions for mooring and some history of the area. This page also has some great photos of the pier from the sea, such as this one, below, taken by Burke Corbett, and used here with thanks to the admins of eOceanic

The author states that the pier was initially built to service the busy copper mines in the area. However, I would expect the roads he refers to, to be visible on the OS maps, and they are not, so perhaps the pier here was quite rudimentary or natural before the current concrete pier was constructed.

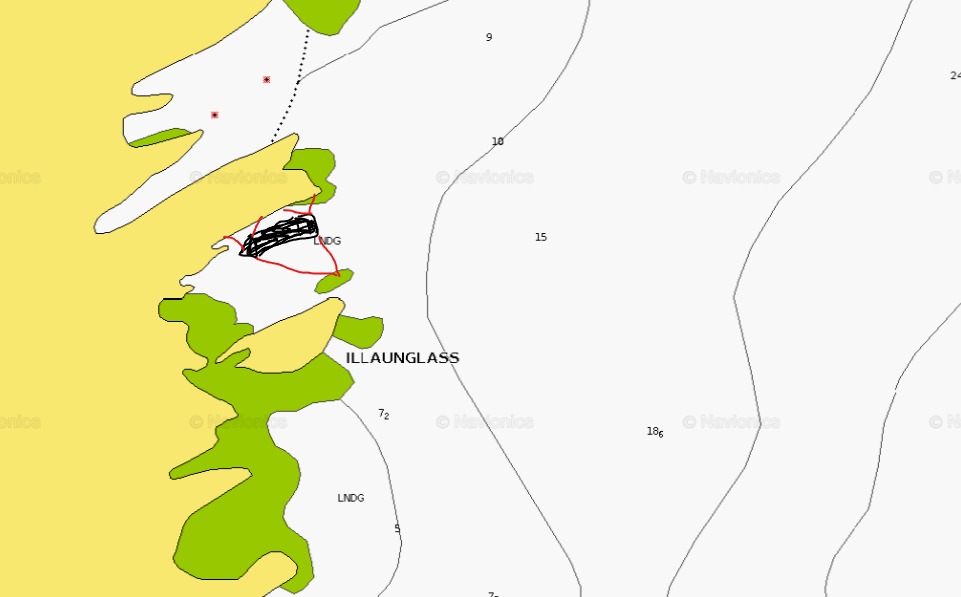

The author of the eOceanic page refers to the feature above on the rock as a ‘steamer turning bollard.’ I had never heard that term before so I turned to my friend Sean O’Mahony, mariner and historian, for an explanation. Here’s what he told me, along with an illustration. Thank you, Sean!

To assist the ship from movement on the jetty, two lines (mooring ropes or hawsers) are extended from the bow and stern to the bollard. This will help to keep the ship reasonably secure from moving backwards and forwards (ranging) along the pier and also prevent her from being pushed hard alongside. This method would only succeed under reasonable weather conditions. I have a feeling that a lot of wooden fenders would also have been employed. My crude drawing demonstrates this with red lines extending to the bollard.

Second, and probably its primary purpose, was to aid in getting the ship off the berth when she is ready for departure. This procedure is known as warping and works like this. The lines to shore from the bow are left go and then using the ship’s windlass the line to the turning bollard is heaved in causing the bow to move outward in the direction of the open sea, at the same time the line from the stern to the bollard is released as are the stern spring lines just holding one line fast to the shore until the turning manoeuvre is complete, When she has turned sufficiently all remaining lines are released and recovered, engine speed is increased and you steam away to somewhere nice…. like the South sea islands…..

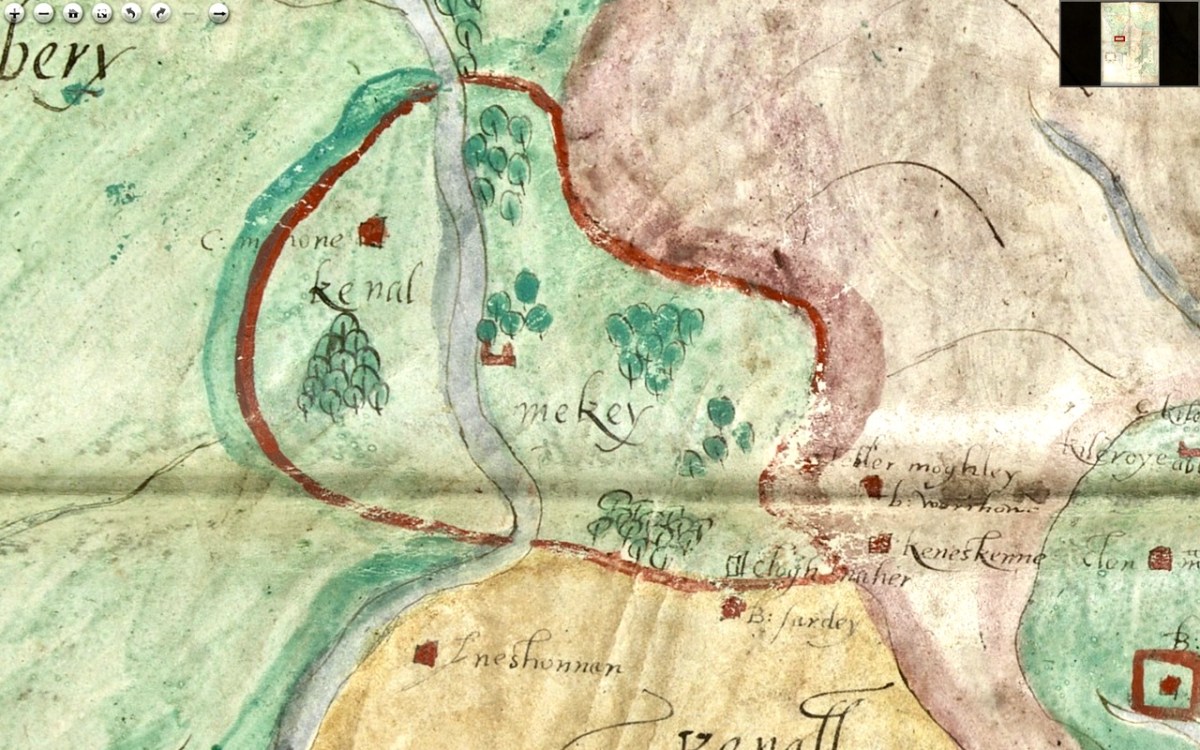

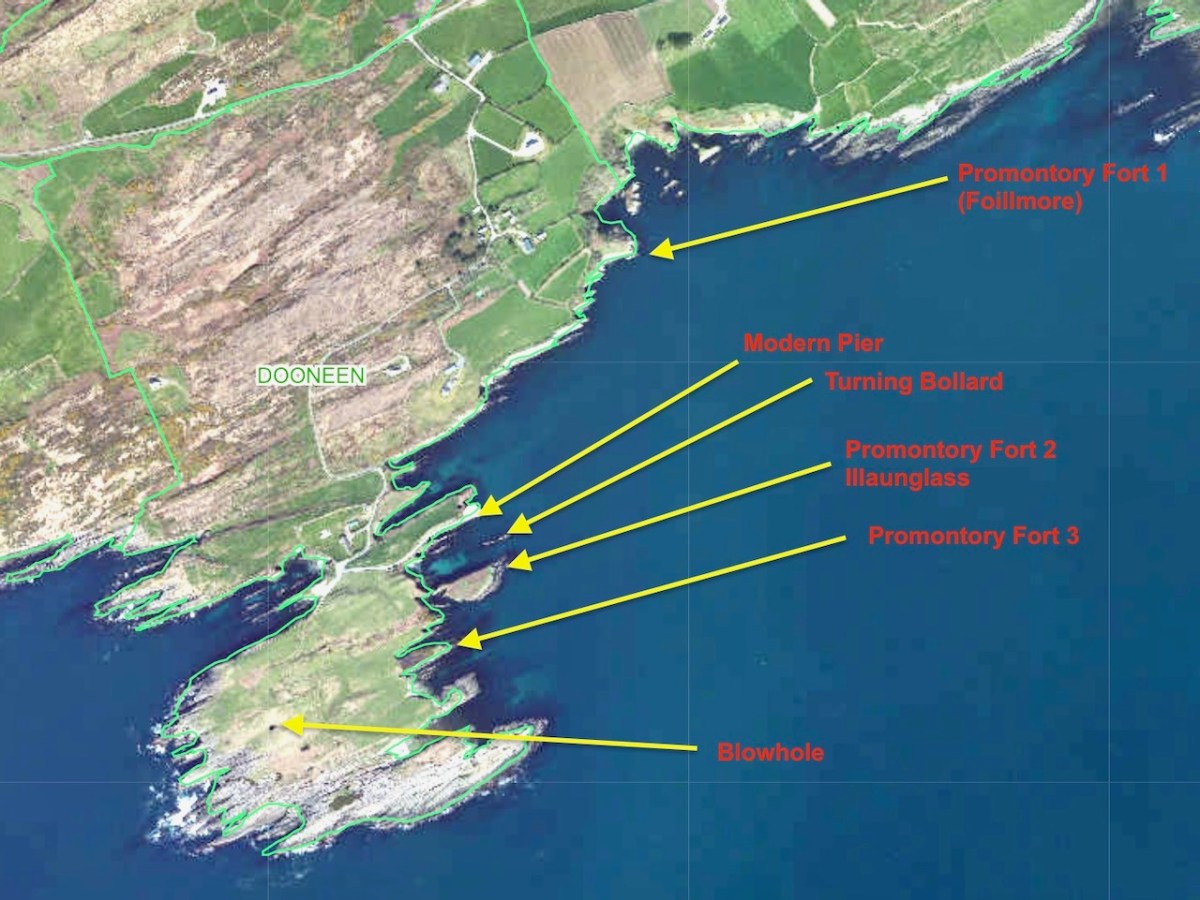

As we might expect with a place with Dún in the title, there is a promontory fort here, and another one next door. (Here’s a good example of a West Cork Promontory Fort.) When studying promontory forts my first port of call is always our old friend Thomas Westropp and indeed Westropp has written about the fort at Gouladoo, on the north side of the peninsula.

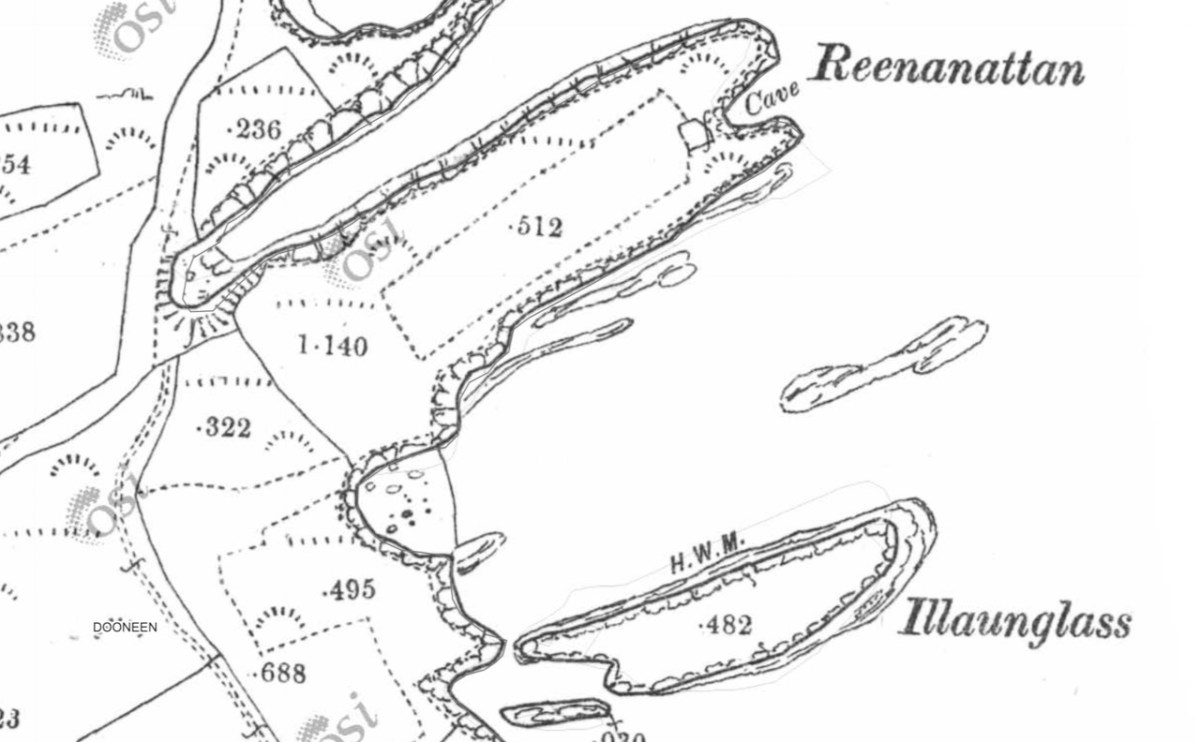

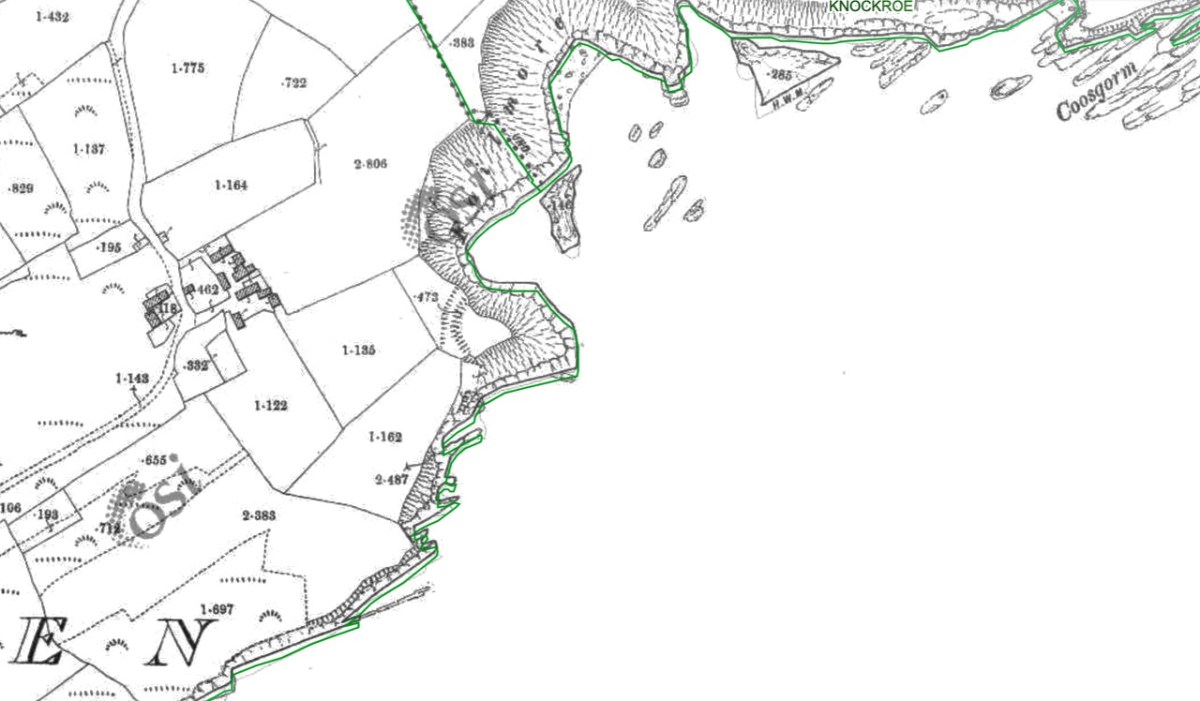

Normally intrepid in his pursuit of the forts. Westropp’s courage failed him when faced, a hundred years ago, with the prospect of travelling on the old, fearfully steep and rough road to this, at that time, remote part of Muinter Bheara. Finding the way ‘insuperable’, he confined his efforts to looking at it with strong field glasses, clear air and light from the Mizen Peninsula across Dunmanus Bay. The fort he describes, as a result of this remote surveillance, and with the help of local informants, appears to be the one further east along the cliffs from Dooneen Pier. It is located on Foilmore (Big Cliff), along from Foilnanoon (Cliff of the Fort). It’s National Monument No CO138-012. It’s Promontory Fort 1 on the map above.

Here’s what Westropp has to say about this fort*:

The high mound and fosse are curved, and bushes grow on the former; inside is a level garth with long grassy slopes down to the cliffs. The rampart, I was told, was “about as high as a man” very steep, “cut by a gap, with a high narrow roadway, only wide enough for a cart to go inside across the ditch” which was “about as deep” as the mound was high – i.e., 5 ft. to 6 ft., making the rampart 10 ft. to 12 ft. high in all. Near it is a small, low peninsula, with little headlands and creeks, Reenanattin (furze point), Coosabriste (broken creek), Carrignagappul, Cooshaneagh (called from horses), and Murkogh. The fort is near Foillmore cliff, and is locally called “the Island of Dooneen” a not unusual term for such forts in Counties Mayo, Clare, Kerry, Cork, and especially Waterford.

Determined to best Westropp and actually visit the fort, I set out, in the company of Amanda and Peter and my sister, to tramp across the fields to it. Alas, we got no further than the farmhouse on whose land the fort is situated, where we were warned that a) it’s crumbling and very dangerous and b) it’s impossible to see anything because of the growth of gorse, trees and scrub.

We abandoned the attempt – I will never doubt Westropp’s good sense again! I contented myself with what is showing on the 19th century OS map, above.

Two more promontory forts are shown on the National Monuments map, presumably identified in the course of the archaeological surveys of the 1980s. It is no longer possible to see the ramparts, banks or ditches of the promontory fort immediately south of Dooneen Pier (above and below) as they have fallen into the sea (like those at Dún an Óir on Cape Clear). This one is called Illaunglass, or Green Island, on the map. According to the National Monument record (CO138-034002) it has a hut site on it. Frustratingly, the details of this record are hidden from view at the moment.

The next one to the south (CO138-035, no. 3 on the map), details also hidden, has a very slight discernible bank, partly covered by a wall, possibly modern (below). However, there is no indication of a ditch or bank in the OS maps, so it is unclear on what basis it has been assigned as a promontory fort.

It is obvious that this area has been important to the inhabitants of Muinter Bheara for a long time, since promontory forts can date as early as the Iron Age (which ended around 500 CE/AD) but are commonly early Medieval, dating up to around 1000 CE/AD.

One more curious feature awaited us on our walk around the ‘Island of Dooneen’ – a blowhole, thankfully guarded by a wire fence. I’d love to go back some time when it’s blowing!

The last thing you see as you head back to the road is the house that was once home to Donald and Mary Grant – the American couple with the White Goats and Black Bees, and the checkered past!

Take a trip out to this part of the Sheeps Head – It’s amazing how one tiny section of coastline can hold such history and magnificent landscape.

*The Promontory Forts of Beare and Bantry: Part III: Thomas Johnson Westropp. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland , Dec. 31, 1921, Sixth Series, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Dec. 31, 1921), pp. 101-115. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25513219