A joint post by Finola and Robert

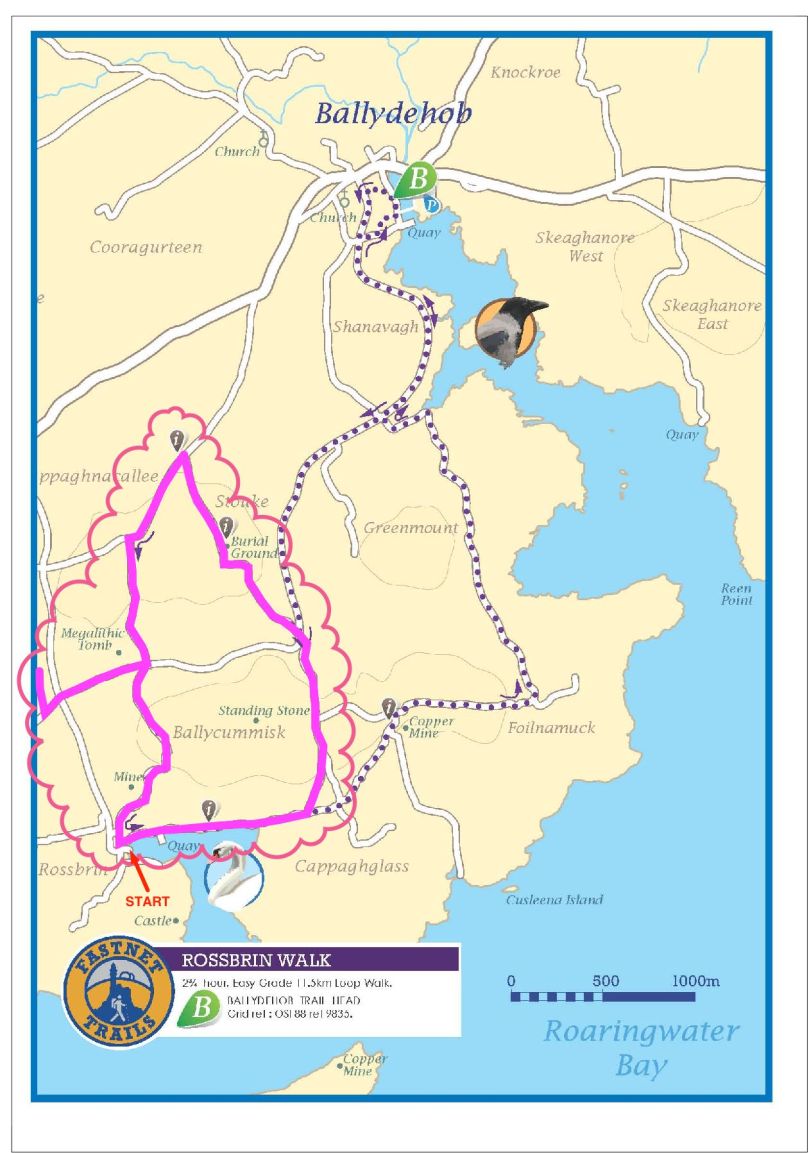

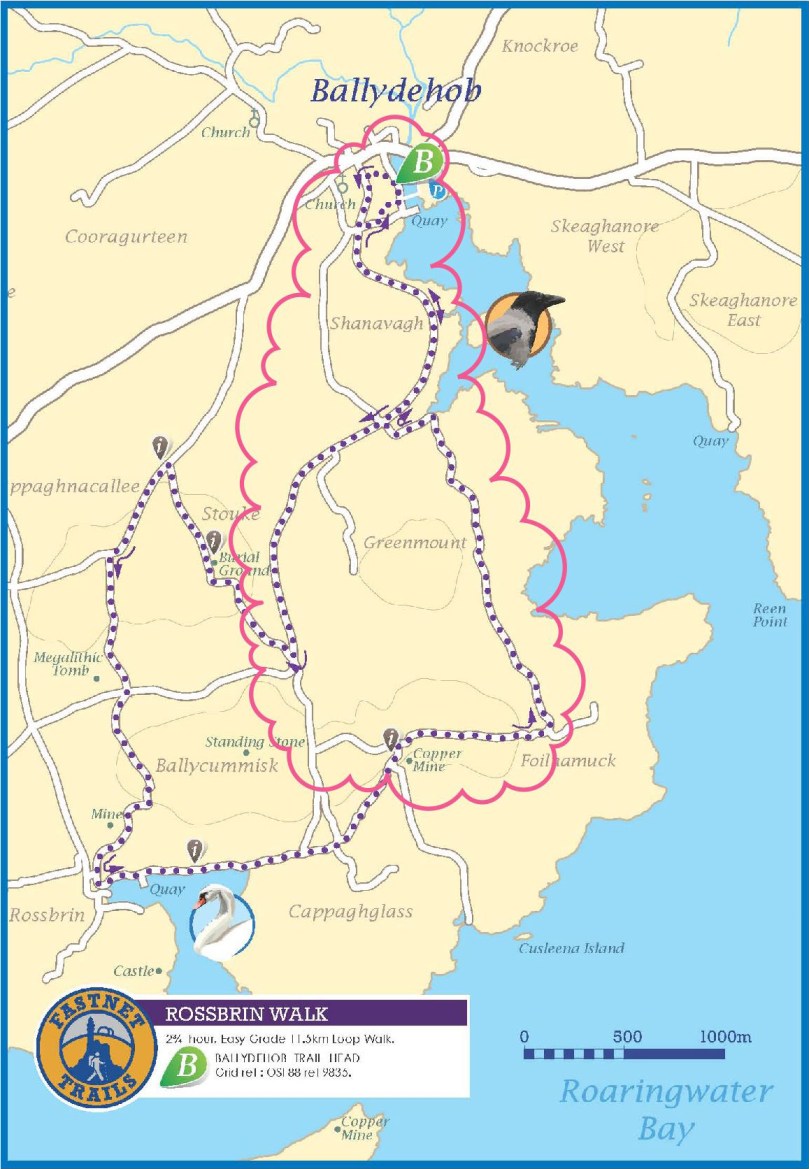

In Part 1 of this trail post, we took you around the first leg of the Rossbrin Loop trail, which we have broken into two shorter rambles.

This one is steeper and climbs higher, but it’s full of interest and you can take it as easy as you like. For this walk, you park at the Rossbrin boat slip, at the eastern end of Rossbrin Cove.

You won’t need off-road boots and you can take the dog. Give yourself two to three hours, depending on whether you decide to do the detour to see the wedge tomb. This is a nice, rambling pace, with lots of time to stop and chat to anybody you meet, admire the wonderful views, take lots of photographs, and maybe indulge in a picnic along the way.

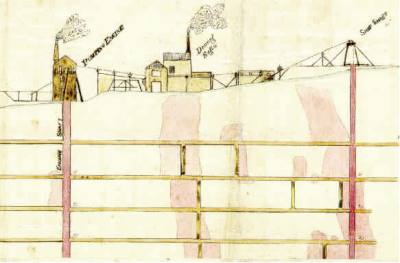

Set off north and turn right after the boat yard and then left up the hill. As you ascend you will see the remains of old mine workings to your left. The earliest records of mining at Ballycummisk refer to 16 tons of ore raised in 1814 and 42 tons in 1815. In 1838 a shaft was sunk 20 fathoms, mainly through barytes and shale. In 1857, 174 tons of ore were sold, mainly copper. By 1861 the mine was recorded as being ‘one of the best developed and very satisfactorily worked.’ The ‘Lady’s Vein shafts’ are marked on the OS 6” map. The Ballycummisk Mining Company worked the mine from 1872. In 1878 a section down to 228 fathoms was noted, but in the same year the mine was recorded as ‘abandoned’. Nowadays some concrete pillars and the slag heap are the most visible remains of the once thriving mine-site.

There are extensive views over the countryside beyond the old mines

At the top of the hill, where you will find a sign to the riding stables, turn left and head through the townland of Ballycummisk with pleasant country views to the west. Once you get to the crossroads you may see a little wayside stall selling vegetables on the honour system. If you’ve brought a backpack, this would be a good place to stock up on carrots, potatoes, or yellow tomatoes.

At this point, we recommend a detour to see the Kilbronogue wedge tomb. Turn left and walk until you reach the next crossroads. Go straight through the crossroads and a short distance on you will see a lay-by on the right side of the road. Step over the wire and find your way up the path that has been generously maintained by the landowner. In early summer this path is awash with ox-eye daisies. It meanders up through a birch plantation until you emerge in a small clearing to find the wedge tomb.

At this point, we recommend a detour to see the Kilbronogue wedge tomb. Turn left and walk until you reach the next crossroads. Go straight through the crossroads and a short distance on you will see a lay-by on the right side of the road. Step over the wire and find your way up the path that has been generously maintained by the landowner. In early summer this path is awash with ox-eye daisies. It meanders up through a birch plantation until you emerge in a small clearing to find the wedge tomb.

Like most wedge tombs, this one is orientated to the west – take a look at our post Wedge Tombs: Last of the Megaliths for lots of information on this class of Bronze Age monuments. This is a lovely example, and we are grateful to Stephen Lynch for ensuring its wellbeing and providing access to it.

Retrace your steps to the second cross roads and turn left up the hill, turning right when your reach a T junction, and then take the left fork at the Y. This is a pleasant country road – farmland stretches on either side, with ruined or abandoned houses dotted here and there among the neat modern farmhouses with their colourful paint and bowery entrances.

In spring and summer the hedgerows are heady with wild flowers of every variety.

Turn right again at the next junction and you will come shortly to the beautiful and atmospheric Stouke burial ground. Although we have read that there are the ruins of an old church in this graveyard, we have never found it. But there are other items of great interest here, the traditional burial place of many island dwellers. In the centre you will find the grave of two priests, Fathers James and John Barry, who were parish priests here during the time of the famine. According to the Historic Graves listing for Stouke “Sarah Roberts who is buried here in this tomb, died at an early age… worked as a housekeeper for the parish priest… When his sister died and was also buried here, Sarah’s coffin was in perfect condition. She was reburied with the parish priest even though she was not a Catholic. People of the parish come to pray at this tomb on the 24th June at John’s Feast Day.”

A little way to the right of this grave is a rock, partially covered by heather, that contains a bullaun stone, known locally as the Bishop’s Head. Once again, according to the Historic Graves entry, “The bishop was confirming children in a nearby church. Red coats came in and beheaded the bishop.”

There are offerings of coins in jars at the bullaun stones, and at the priests’ grave. Leave one too, along with a prayer or wish for a loved one.

From Stouke the road drops down to a cross roads. Go straight through and start to climb again up to Cappaghglass. Ignore the left turn and carry on until you reach a Y junction. Take the right fork, pass all the ripe blackberries (if you’re able) and as you crest the hill the whole of Roaringwater Bay is laid out before you. Few views in the country can equal this one for sheer scope: all the islands in Carbery’s Hundred Isles come into view, The Baltimore Beacon gleams on its rocky outcrop to the east, while the Fastnet Rock sits sturdily on the horizon, and the Mizen Peninsula stretches away to the west.

Descend the steep hill, turning right at the T junction, and meander down to Rossbrin Cove.

Now a peaceful boat harbour, Rossbrin in the 15th Century was the domain of Finghín O’Mahony, the Scholar Prince of Rossbrin, a man who used the riches extracted from taxes paid by Spanish and French fishermen to fund a centre of learning here in Rossbrin where scribes and learned men wrote and translated books which still exist today. The ruined section of the castle still standing gives little evidence of the erudite court that was once respected throughout Europe. A fish ‘palace’ for processing pilchards once provided employment to the people of Rossbrin, but little trace remains of it, or the holy well at the shore that once attracted those seeking cures for their ailments.

If the weather’s warm and the tide’s in, this is a good spot for a dip. No? Well, a photograph, then.

We hope you’ve enjoyed the two Rossbrin Loop walks – do let us know how you got on.